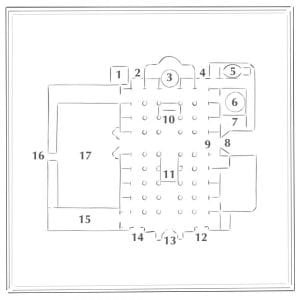

The church of San Sebastián is a Gothic-Mudejar temple originally built between the 15th and 16th centuries as a hermitage on the outskirts of the city. It has undergone profound transformations throughout its history, especially during the 19th and 20th centuries, in relation to the appearance of the Porvenir neighbourhood around it. It has a rectangular floor plan divided into three naves by pointed arches. The area of the presbytery and the sacramental chapel stand out from the floor plan, at the head of the Epistle nave. The church is the headquarters of the Hermandad de la Paz, which processes on Palm Sunday.

History

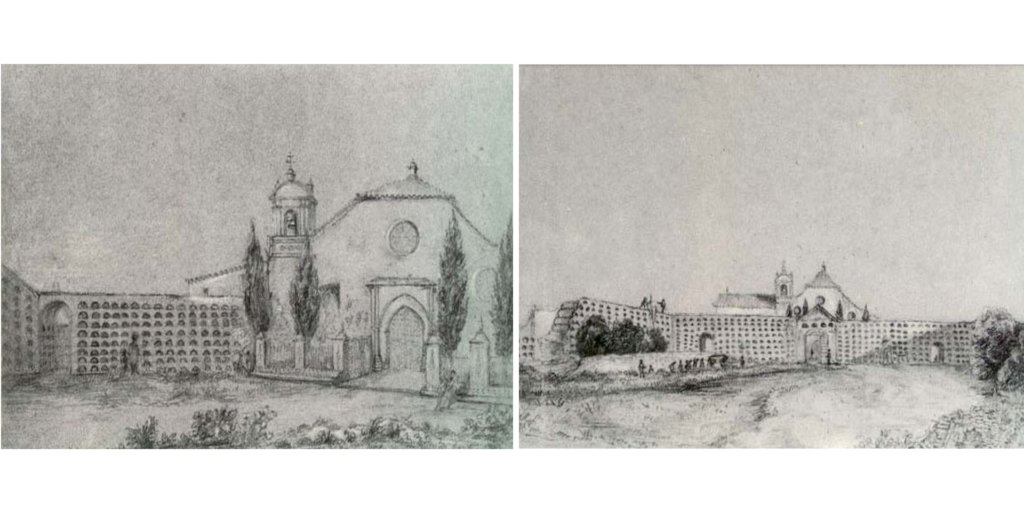

The origin of the church is a hermitage that was built on this site at the end of the Middle Ages in honour of San Sebastián, a saint who was asked for intercession in the event of epidemics. In the 19th century, the first cemetery outside the city walls was built near the hermitage. It should be remembered that for most of our history, burials took place in churches or in their surrounding areas, with the consequent health problems that this practice entailed. There are two drawings by the English traveller Richard Ford made in 1831 in which the cemetery and the primitive hermitage appear. The cemetery of San Sebastián lost importance after the construction of the municipal cemetery of San Fernando in 1852 and ten years later its demolition would begin, as recalled by an inscription at the foot of a cross that is currently located in front of the church as a commemorative monument. After the cemetery disappeared, a reform of the old hermitage was undertaken. It was probably at this time, in the mid-19th century, when the current presbytery was added, since it is known that there was originally a Gothic style one and the current one is covered by a hemispherical dome in the Baroque style.

From the beginning of the 20th century, with the preparations for the Ibero-American Exhibition of 1929, the creation of the Porvenir neighbourhood in the area of the old hermitage was accelerated, with the result that the temple was reformed several times, as it gained importance as an auxiliary to the parish of San Bernardo.

In 1939 the Hermandad de la Paz was founded with headquarters in this church, which entailed new reforms, such as the opening of the south doorway for the exit of the floats or the construction of the brotherhood house, built under the direction of Rafael Arévalo y Carrasco in 1941. In 1956 the church was definitively established as a parish and has come down to our days consolidated as the centre of religious life in the neighbourhood.

Outside

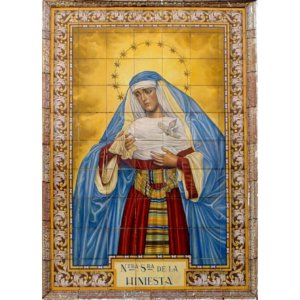

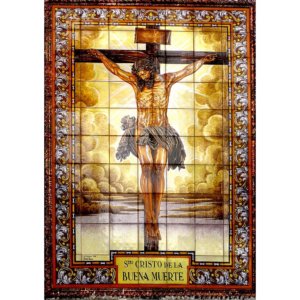

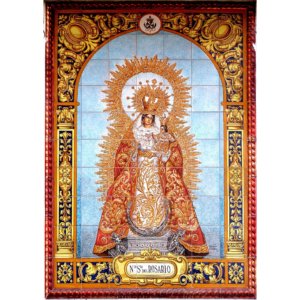

On the outside, the church is surrounded by annex buildings, with only the south and east façades remaining free. On the south side, the buttresses supporting the walls can be seen and it has a simple doorway in the area closest to the head. It was opened in 1940 to allow passage through and is made up of a simple semicircular arch framed by a moulding of exposed brick. To the right of the door is a beautiful ceramic altarpiece with the Christ of Victory, made by Alfonso Magüesín de la Rosa in 1989. In the background there is a landscape in which the silhouette of the Plaza de España can be distinguished. The ceramic altarpiece dedicated to the Virgin is very close, next to the entrance to the fenced area around the church. It was made by Antonio Morilla Galea in 1977 and it highlights the beautiful contrast between the whiteness of the figure of the Virgin and the black background.

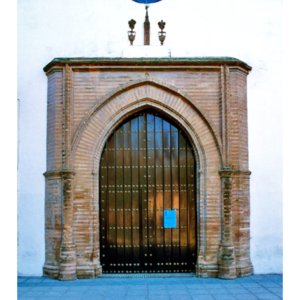

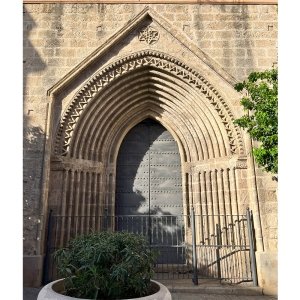

The main façade is the one facing east, at the foot of the church. In its centre we find a magnificent Mudejar doorway, probably built in the 15th century. It is formed by a pointed arch, framed by a structure that stands out from the rest of the façade, built from rows of bricks in alternating colours. It is very beautiful despite its simplicity and is clearly related to other similar doors that we find in Seville, such as that of the church of the convent of Santa Paula or that of the chapel of Santa María de Jesús. Above the door we find the coat of arms of the Cathedral, the Giralda between two jars of lilies, a symbol of the patronage of the cathedral chapter. This emblem does not appear in Richard Ford's drawing of 1831, so it must have been added later.

At the top of the façade there are three oculi, one in the centre and two on the sides, which serve to illuminate each of the naves. On the left stands a simple bell gable, with a single bell and topped with a curved pediment.

Interior

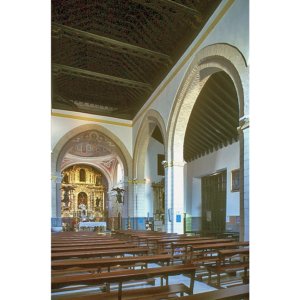

Inside, the space is divided into three naves, with the central one wider and higher than the side ones. Large pointed arches resting on cruciform pillars separate the naves. Another large pointed arch separates the central nave from the presbytery, like a triumphal arch. Most of the walls are plastered in white, with the area of the pillars imitating ashlar and leaving the brickwork on the arches exposed. A 20th-century tiled plinth with geometric shapes runs throughout the interior. The roof is covered by wooden coffered ceilings in the neo-Mudejar style, with a pair and knuckle in the central nave and hanging in the side ones.

From the rectangular space formed by the naves, three spaces stand out at the head. The presbytery is located in the centre, the sacristy at the head of the right nave and the chapel occupied by the Brotherhood of Peace at the head of the Gospel nave.

The presbytery is a quadrangular space covered by a hemispherical dome on pendentives that is not visible from the outside of the temple. In all probability, it was originally covered by a pointed vault, as occurs in most of the Gothic-Mudejar churches in the city. The current dome must have been built during the reforms undertaken in the 19th century. The walls are decorated with contemporary paintings with geometric motifs, plants, fake architecture and angels. The pendentives follow the tradition of serving as a support to accommodate the Evangelists, who are represented by their symbols.

The altarpiece is in neo-baroque style, made in the 20th century. It is divided into three sections and two horizontal bodies. In the main niche we find a magnificent sculpture of the Virgin and Child, known as the Virgin of the Meadow. It was made by Jerónimo Hernández around 1577 and is an outstanding example of Renaissance sculpture in the city. The Child Jesus appears blessing with a sweet gesture while the Virgin holds a pear in her right hand. It should be remembered that this image acted as patron and protector of market gardeners and country people in this area of Seville.

On the side streets are the sculptures of San Pedro and San Roque. In the centre of the second body is San Sebastián, the patron saint of the temple, flanked by San Jacinto and Santo Domingo de Guzmán. All the sculptures seem to be original from the 18th century, although they were probably re-painted later.

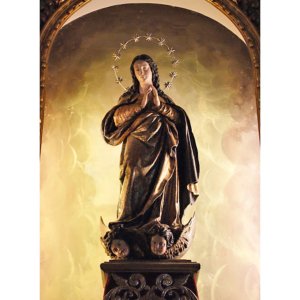

Other sculptures and paintings are displayed on the walls of the naves. One of the most notable is a carving of the Immaculate Conception from the 18th century, which presides over a stucco altarpiece in neoclassical style. There are also some carvings from the 20th century, such as the Sacred Heart, which presides over a neo-Baroque altarpiece. Among the paintings, we find several copies of originals by Murillo and some other Baroque paintings, such as the "Martyrdom of Saint Lucy" (Francisco Varela, c. 1637), the "Annunciation" or the "Marriage of the Virgin". From the same period there are representations of various saints, such as Saint Lawrence, Saint Agnes or Saint Sebastian, and an interesting "Virgin of Guadalupe", a copy of the Mexican original made by Antonio Torres in 1740.

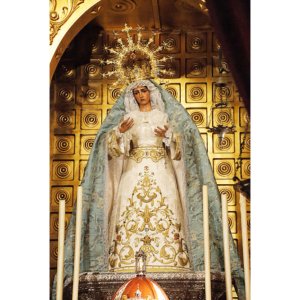

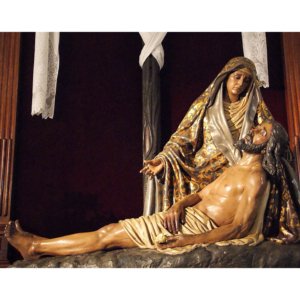

As we said, at the head of the left nave is the sacramental chapel, where the titular images of the Hermandad de la Paz are worshipped. The chapel is covered by a groin vault with a lantern in the centre and presided over by a neo-baroque altarpiece. In the centre we find Nuestro Padre Jesús de la Victoria, a sculpture made by Antonio Illanes Rodríguez in 1940. It forms part of a float in which Jesus is seen taking the cross to carry it on the way to Calvary, although when it is in its chapel the image is logically shown without the cross. On the left is the image of María Santísima de la Paz, made in 1939 also by Antonio Illanes, who is said to have been inspired for the face of the image by the facial features of his wife, Isabel Salcedo. When it comes to the procession, the image stands out for the white and silver tones of its float, both in the canopy and in the figure of the Virgin herself. This whiteness is a clear sign of the devotion to Peace and creates a very unique and iconic image during Holy Week in Seville. The same artist also made the sculpture of Saint John that occupies the niche on the right of the altarpiece.