SUSANA BEN SUSÓN (LA SUSONA)

(15th century)

The woman popularly known as "la Susona" is probably the most famous figure of the old Jewish quarter among the Sevillians. She lived in the street that today bears her name at the end of the 15th century and was the daughter of Diego ben Susón.

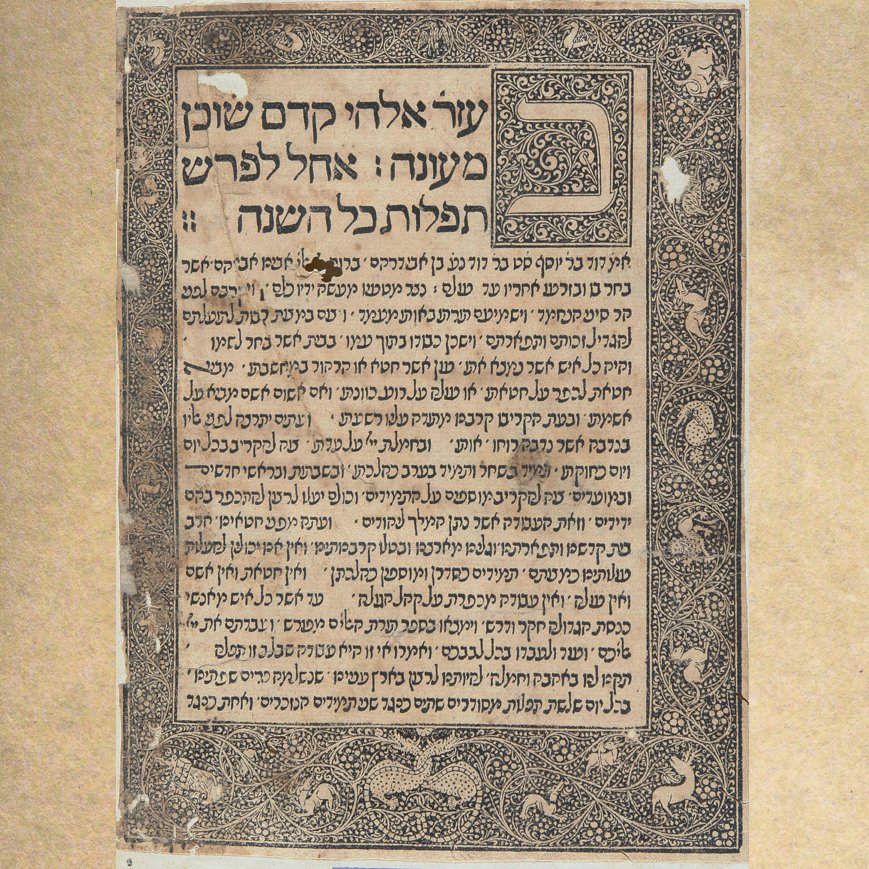

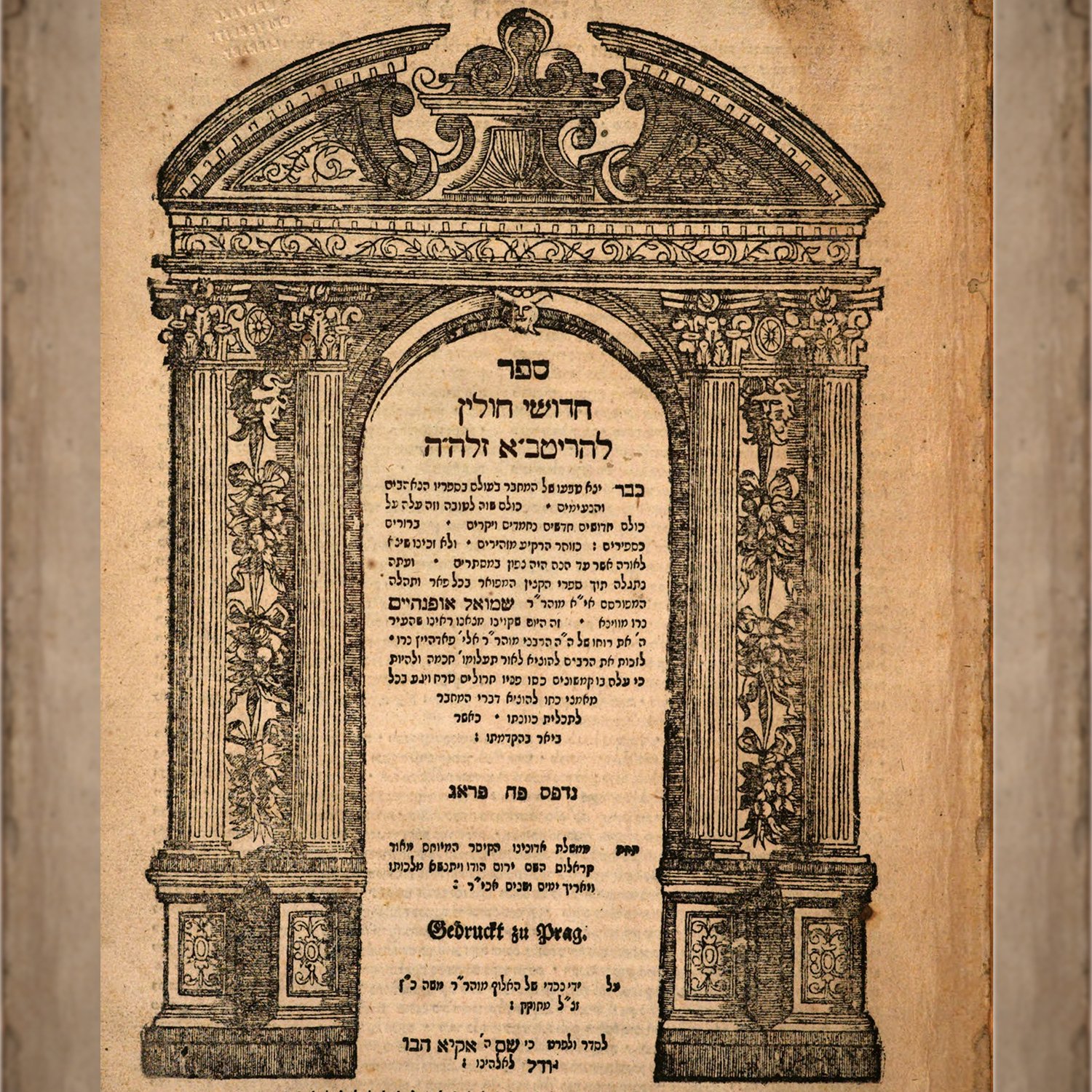

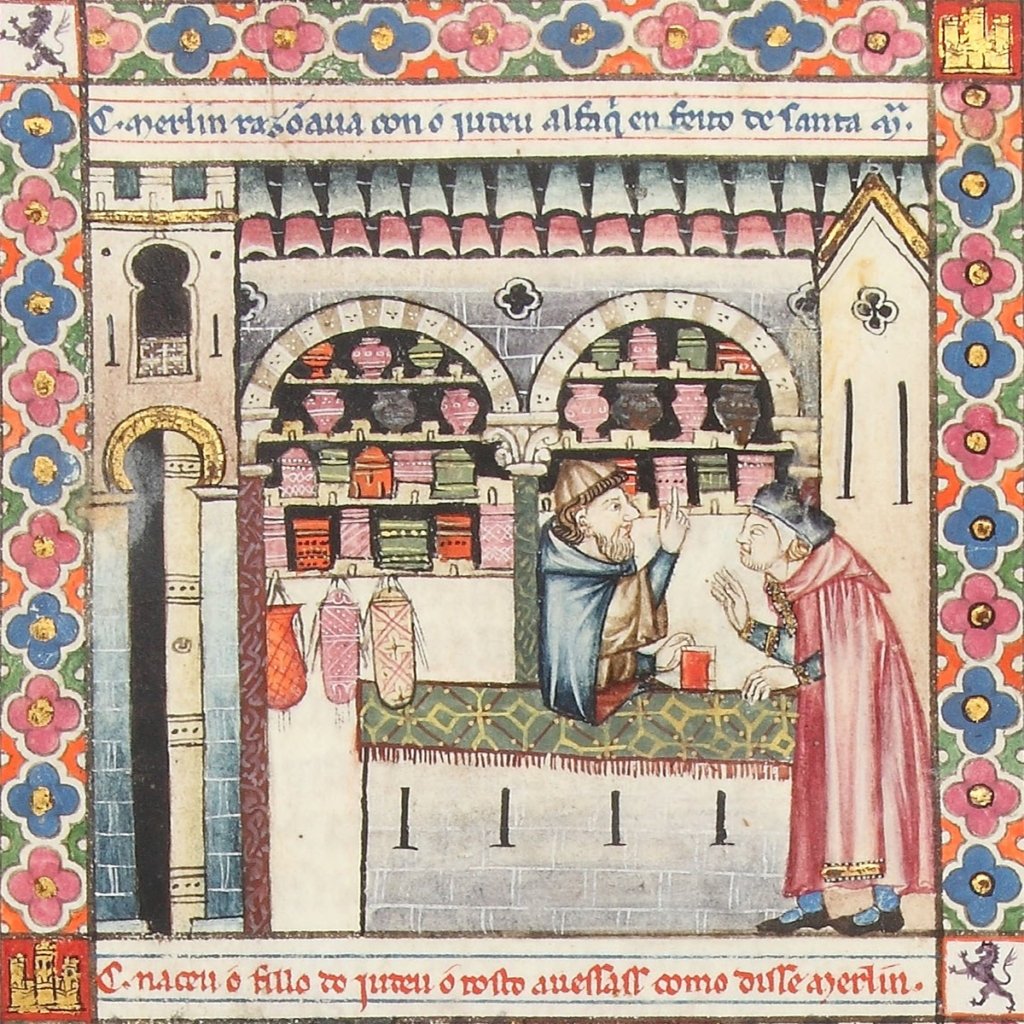

We know that the events that made her famous occurred around 1481, when the members of the Inquisition sent to Seville were working hard to ensure that those Jews who adopted the Christian faith did so sincerely. Throughout the 15th century, a large part of the Sephardic Jews decided to convert to Christianity as a way of avoiding the terrible and growing conditions that the Mosaic faith brought to the peninsular kingdoms.

According to the most widespread version of the story, Susona's father was one of these "new Christians" who had changed religion more out of pragmatism than conviction. When the Inquisition began to order arrests and imprison suspected converts, fear grew among the members of this community, to the point that some of them considered organizing a revolt that would end the lives of the inquisitors. Apparently, Diego ben Susón was one of the ringleaders of this revolt.

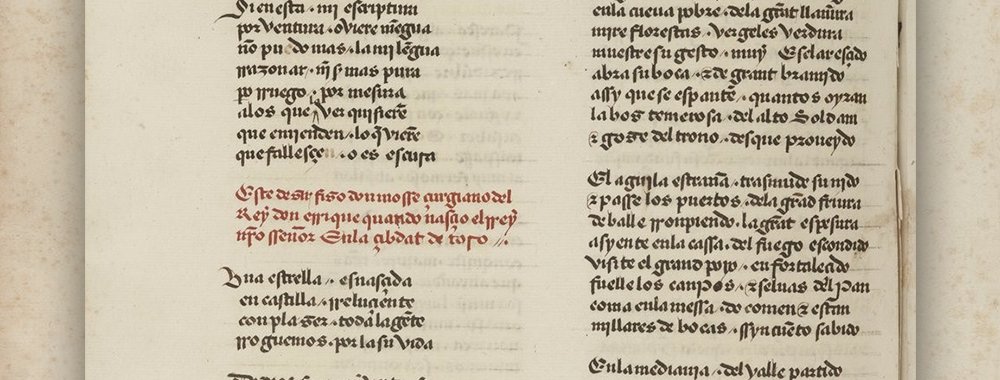

From then on, the versions of the story differed greatly. We will stick here to the one told by Mario Méndez Bejarano in his "History of the Jewish Quarter of Seville" (1914):

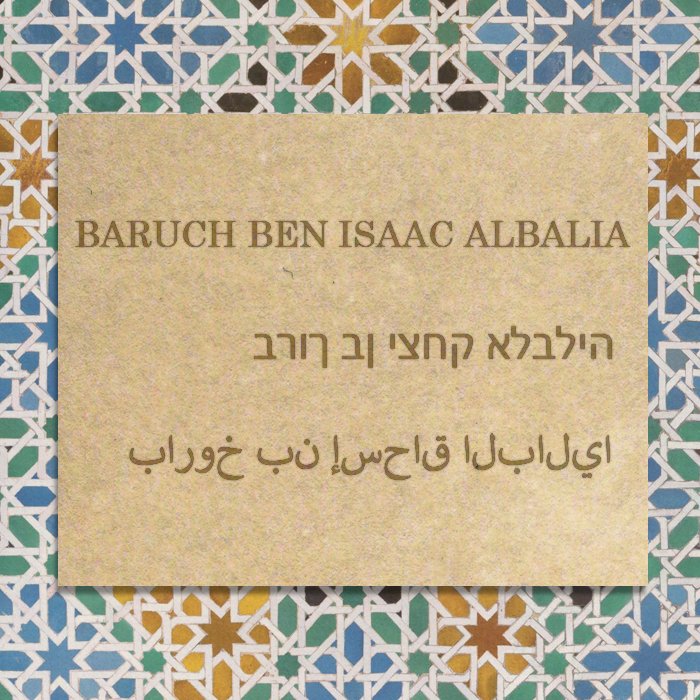

Susan [Diego ben Susón] had a daughter of surprising beauty; she was called "the beautiful woman" and commonly called Susona; she denounced the plot to the inquisitors but it is most likely that she was not the one who informed on her, since she received in her house a Christian gallant who, in his religious zeal, must have reported to the Holy Office the confidences she shared with him. Whatever the case, the conspirators were surprised with weapons in Benedeva's house by a hundred men and were locked up in the dungeons of the Inquisition. The main conspirators: old Susan, the learned Abolafia, the venerable old man Benedeva and the rich Sauli and Torralba were burned on February 6, 1481. It is said that when Susan went to the stake, the rope she wore around her neck dragged along the ground. Maintaining his Andalusian charm until the last moment, he said to those who accompanied him: “Take this Tunisian cap off me.”

Reginaldo Romero, bishop of Tiberias, did everything possible to force Susana to profess, but the sensual pleasures of the Jewess were poorly suited to the discipline of the cloister and leaving the convent before professing she lived with various lovers, of increasingly lower status, to end up in the arms of a spice seller. In her will, the “beautiful Jewess” expressed the wish that her head be placed on the door of her house “where she had lived badly, as an example and punishment for her sins.”

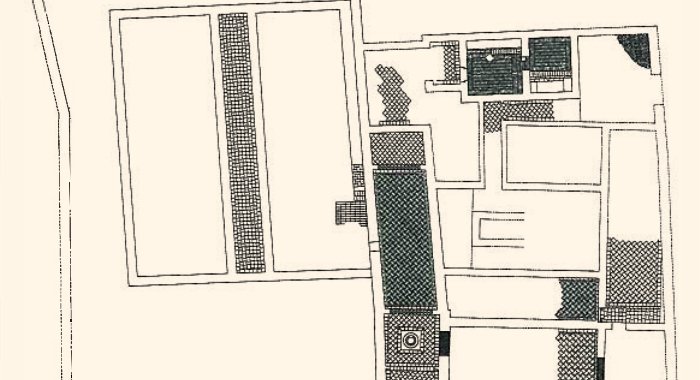

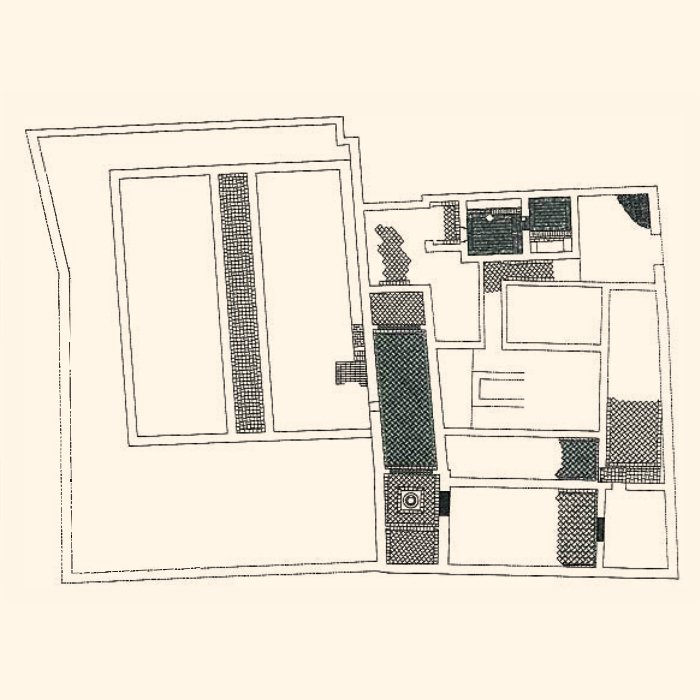

According to tradition, Susana’s skull was displayed on the façade of her house for centuries. Over time, the place began to be called the “street of Death,” given the logical association between this concept and the skull. It was called that until 1845, when it was renamed to its current name, “street of the Susona". The exact location of the house and where the skull was displayed are unknown. In the "Historical Report of the Jewish Quarter of Seville" (José María de Espinosa, 1820) a manuscript is cited in which this reference appears:

His skull is on a wall, opposite Calle del Agua at the exit of the narrow passage that leads to the Alcázar where the water flows.