This small church was built at the initiative of the city's carpenters' union, and hence its dedication to Saint Joseph, patron saint of woodworkers. It is known that the carpenters already had a temple in this area in the 16th century, but its dilapidated state meant that it had to be demolished. The current temple was built in two phases during the 18th century.

The first of these was directed by Pedro Romero and concluded in 1717 with the construction of the only nave of the chapel. The second was completed in 1766 under the direction of Esteban Paredes, completing the main chapel and the exterior of the temple. The church reached the 20th century in a state of practical ruin and in 1931 suffered a fire in which it lost the roof and part of its wall paintings. Fortunately, she was able to be rehabilitated and returned to the cult.

As we said, it is a small church, with a single nave and transept slightly marked in plan. It has two exterior doors, one at the foot and another on the Gospel side.

The main doorway is made of brick with a showy Baroque style that manages to convey the sensation of monumentality despite its small dimensions. Two pilasters support a divided curved pediment, in the center of which opens a niche with the image of San José, designed by Lucas Valdés in 1716. On both sides, two richly framed medallions with the busts of San Fernando and San Hermenegildo, and on the central niche, a third medallion with a representation of San Juan Bautista in youth.

On both sides of the door, two niches housed the images of San Joaquin and another saint, identified as San Jason or San Teodoro de Amasea. To avoid damage, both are currently kept in the sacristy of the church, being replaced by two images made in resin by the contemporary sculptor Jesús Curquejo Murillo. One of them is a copy of the previous San Joaquín, while the other is a tender representation of Santa Ana with the girl Virgin.

The side doorway can be dated to the same period as the main one and its central element is a beautiful relief that represents the Betrothal of the Virgin and Saint Joseph, attributed to the great eighteenth-century sculptor Cristóbal Ramos. On the molding that frames this scene, four high-quality images gracefully rest despite their profound deterioration. On the first level, Saint Peter (today headless) and Saint Paul, and on the main scene, two allegorical figures representing virtues attributed to Saint Joseph: Meekness, holding a lamb, and Chastity.

Inside, the only nave of the temple is covered with a barrel vault resting on transverse arches, and an elliptical dome with a blind lantern rises over the transept. The profuse sculptural and pictorial decoration of the temple make the Chapel of San José an exquisite little jewel of Sevillian Baroque.

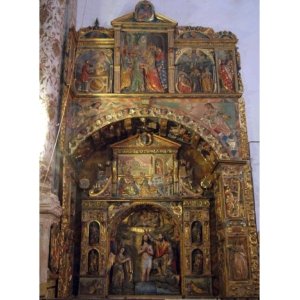

The main altarpiece was designed by the Portuguese-born sculptor Cayetano de Acosta, one of the most outstanding artistic figures of the 18th century in the city. On the bank, the main body is divided into three streets by means of stipes, although the profuse decoration that covers practically every centimeter makes it difficult to distinguish this structure. In the central niche is located the head of the temple, San José, in a sculpture of the circle of Pedro Roldán. In the stipes that frame this niche are the figures of San Joaquín and Santa Ana, parents of the Virgin, attributed to Pedro Duque Cornejo, another of the great sculptors of the 18th century in Seville.

On the Tabernacle, there is an image of the Immaculate Conception, and on both sides, in the side streets of the altarpiece, we find San Juan Bautista and San Juan Evangelista, under two medallions with high reliefs of San Sebastián and San Roque.

In the upper part of the altarpiece, a series of children and young angels complete the composition, and in the center of the attic is the image of God the Father in an attitude of blessing.

On both sides of the transept there are two altarpieces, with the same chronology as the main one and also with profuse decoration. The one on the right gives access to the sacristy and the one on the left is presided over by a sculptural group with the Coronation of the Virgin.

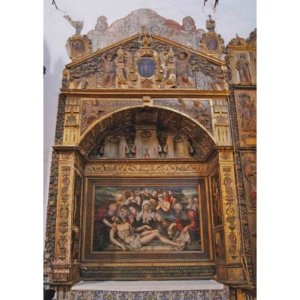

On the sides of the nave, framed under semicircular arches, there are two other altarpieces. Both have been dated to the 18th century. The one on the right has in its center a beautiful set with The Betrothal of the Virgin on an interesting and classic architectural background, while the one on the left is presided over by an image of Santa Ana.

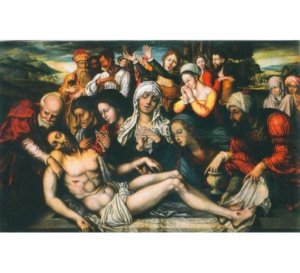

The paintings that decorate the vaults and arches have been dated to the last third of the 18th century, a century to which the various canvases on the canvas walls also belong. As an exception, we find a beautiful painting from the 17th century that represents Rest on the flight to Egypt. It is by an anonymous author who seems to follow in style the work of the Italian Paolo Veronese.

[mapsmarker map="2" lat="37.390028" lng="-5.994639" zoom="18" height="300" heightunit="px"]