In the 13th century, the Christian kingdoms advanced decisively towards the south, leaving the Reconquista practically finished with the exception of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada, which would remain in Muslim hands for two more centuries, until 1492. The Crown of Aragon incorporated Valencia and the Balearic Islands, while Castile expanded through Extremadura, the area of Jaén and western Andalusia. This concluded the historical process by which the Jews went from living under Islamic rule to living in Christian territories, so it is a good point to describe the general panorama in which the Jewish populations in the Peninsula found themselves.

In the Crown of Castile, the most important Jewish quarter was by far that of Toledo.

- In the area of Extremadura, Cáceres, Plasencia and Badajoz stood out.

- In the north and centre of Castile, the Jewish quarter of Burgos stood out, in addition to that of Toledo, which, as we said, was the most important. Other Jewish quarters of similar size were found in Palencia, Sahagún, Villadiego, Carrión de los Condes, Valladolid, Medina del Campo, Peñafiel, Ávila, Segovia, Soria, Medinaceli, Guadalajara, Cuenca, Huete and Talavera.

- In the western area there were fewer Jews, but the Jewish quarters of León, Salamanca and Zamora can be mentioned.

- In the southeast, the Jewish quarter of Murcia is worth mentioning.

In the Crown of Aragon, Barcelona and Zaragoza stood out, far above all the others.

- In Aragon itself, we can mention Calatayud, Huesca, Teruel, Jaca, Monzón, Barbastro, Daroca, Tarazona and Alcañiz.

- In the area of Catalonia, apart from Barcelona, Gerona, Perpignan, Lérida, Tarragona, Tortosa, Vich, Manresa, Cervera, Tárrega, Santa Coloma de Queralt, Montblanch and Besalú stood out.

- In the Kingdom of Valencia, the Jewish quarter of the capital city stood out, in addition to those of Castellón, Játiva, Murviedro and Sagunto.

- In the Kingdom of Mallorca, the Jewish quarter of its capital, Palma, was important.

In Navarre, the most important Jewish quarters were in Tudela, Pamplona and Estella. There were other smaller ones in centres such as Olite, Tafalla, Peralta or Puente de la Reina.

The social and economic background of the inhabitants of the Jewish quarters was very diverse, but the most numerous were artisans and small traders. There are many references to Jews who were dedicated to agriculture, viticulture, industry, trade and various crafts. There are tailors, shoemakers, jewellers, potters, dyers, blacksmiths... Many of them owned small shops that were sometimes also workshops, mainly with textile products. There were also people in the Jewish quarters who were mainly dedicated to intellectual tasks, such as rabbis or Talmudic scholars, who often received funding from the community.

However, it was the money business that brought them their wealth and influence. Kings and prelates, nobles and farmers all needed money and could only get it from Jews, to whom they paid 20 to 25 percent interest. This business, which the Jews were in a sense forced to engage in in order to pay the numerous taxes imposed on them, as well as to obtain the obligatory loans required of them by the kings, led to their being employed in special positions, such as "almoxarifes", bailiffs, tax collectors or tax collectors.

Jews did not always live in groups, but it was the most common option in most cities. Jewish quarters usually occupied central areas of the city, close to the centers of political and religious power. In fact, in cities with a cathedral, the Jewish quarter was usually located very close to it. On many occasions, as in the case of Seville, there were walls or other types of fixed boundaries to separate the Jewish quarter from the rest of the city.

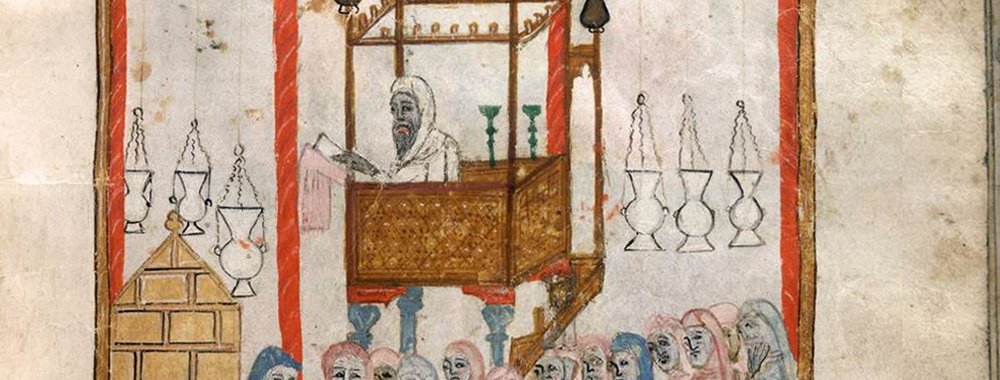

The "aljamas"

The word "aljama" of Arabic origin designated both the Jewish quarter itself and the legal institution that governed and represented it. In Hebrew it was called "cahal", equivalent to the municipality for Christians. They had their own legal system known as "tacanot" and an institutional framework with political, cultural and religious functions. There was a main rabbi, sometimes called "nasí" or prince, who was in charge of the highest representation of the aljama before the authorities and whose position depended on royal appointment. In addition, there were councils dedicated to specific issues, such as fiscal or faith-related matters. They were made up of judges or "dayanim", who Christians also called rabbis. In addition, in Castile the sources also mention the elders or "old men" and the adelantados (called "muccademín" in Hebrew). Normally they tended to belong to distinguished families and were in charge of various functions related to the administration of the aljama.

The rabbis were not part of the administrative structure but had great influence over their fellow citizens, being empowered to dictate any type of provision necessary for the maintenance of moral and religious discipline.

In Castile, assemblies with representatives of the different aljamas were frequent from the 14th century onwards, making decisions that affected the common interests of the Jewish population, both in relation to religious and fiscal matters or of any other nature. In addition, since the time of Alfonso X there existed the figure of the rab major, a position with authority over all the aljamas, who was mainly in charge of tasks related to taxation and the administration of justice. These "central" institutions did not exist in the Crown of Aragon, where the aljamas were autonomous and generally jealous of their independence.

Among the functions of the aljama was also that of watching over the morality and good customs of the inhabitants of the Jewish quarter. To this end, they had the power to dictate the "herem", which was an anathema imposed on those people whose behavior was considered contrary to the interests of the community. It was a very severe punishment, since people who suffered it were removed from the community and their neighbors were forced to ignore them. They also severely punished the "malsines", who were a kind of informer much hated by the Jews. By royal concession, some communities even had the power to dictate the death penalty for these malsines, an exceptional power unknown among the Jews of other European countries.

As regards fiscal policy, in addition to the taxes that had to be paid to the royal treasury, the aljamas had their own taxes, which generally taxed meat and wine. They also regulated other aspects of neighbourhood life, such as market prices, building regulations or the prohibition of gambling.

In larger Jewish quarters, the aljama also provided basic assistance for the poor and offered first-class education for children. In addition, there were more specialised schools for the children of well-off families, where private tutors taught not only the Talmud but also poetry, medicine or astronomy.

From a social point of view, it can be said that the Jews were divided into two large groups:

- On the one hand, the wealthiest families formed a kind of privileged aristocracy. Its members often held positions in the administration of the aljama and often even in that of the kingdom. Their way of life was sometimes similar to that of Christian high society, with lifestyles not very in keeping with the dictates of the Hebrew religion.

- On the other hand, there was the social majority, generally artisans, shopkeepers and all kinds of professionals in a rather modest economic situation.

For most of the Middle Ages, most Jews accepted this difference in social class without much difficulty, but in the 13th century, theories related to the Kabbalah began to spread and, as a result, there was greater conflict. Social struggles would increase and become especially intense during the 14th century.