The Old Silo of the Cathedral Council (Antigua Cilla del Cabildo de la Catedral) is an 18th century building that stands on Santo Tomás Street in Seville. Throughout its history it has undergone various remodeling in relation to the different uses it has received. Currently it is the headquarters of the General Archive of the Indies, a condition it shares with the Antigua Lonja de Mercaderes, which stands just across the street.

Its construction took place in 1770 to serve as a grain warehouse for the Cathedral Chapter. Apparently, the place they had been using for this purpose was seriously damaged in the 1755 Earthquake, so it was necessary to undertake this project. There is no certainty about the architect who directed the work. Some authors point to Pedro de Silva, who was the chief architect of the Archbishopric. However, the Navarrese Lucas Cintora is also mentioned, who would later be mainly responsible for the transformations in the Lonja building to adapt it to its new use as an Archive.

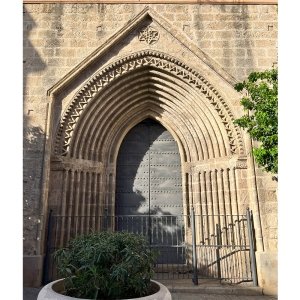

For the construction of the façade, a fragment of the wall that joined the Alcázar with the Torre del Oro was used. In fact, even today we find one of the towers attached to the façade of the building. It is a simple square tower, dating from the late 12th century or early 13th century.

La Cilla lost its use as a warehouse in the 20th century and for a short period was the headquarters of the Royal Asturian Mines Company. In 1972 it was decided to completely renovate the property to make it the headquarters of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Seville. The architect from Cádiz Rafael Manzano Martos was in charge of directing the works on this occasion.

A new stage in the history of the old cilla would begin around the year 2000, when the process began to incorporate it as a complementary headquarters for the General Archive of the Indies. The works were completed in 2005 and the building was then configured with its current characteristics.

La Cilla was originally designed as a rectangular building with two floors. The naves are covered with hollow vaults supported by rectangular pillars and marble columns. It currently has two more floors, one in the basement and another under the roof, added in successive transformations to adapt the property to a museum and, later, an archive.

The façade repeats the compositional scheme of the Lonja building that is located directly opposite. La Lonja responds to the design of the great Renaissance architect Juan de Herrera and introduced a bichrome on its façade that was enormously successful in Seville.

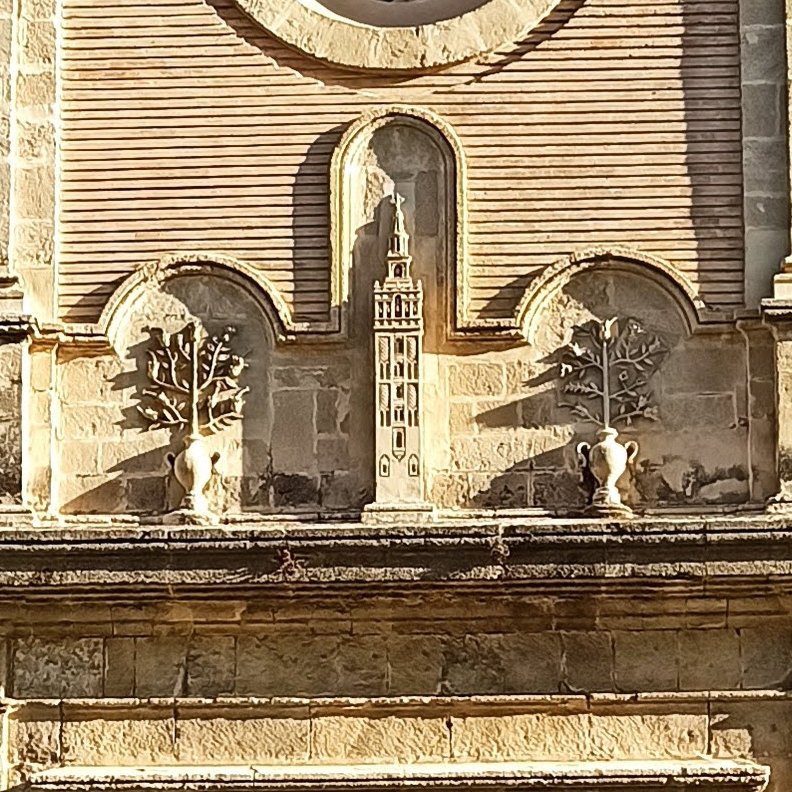

We see this bichrome repeated on the façade of the cilla, with the stone areas in lighter tones and the brick facings with a more reddish color. The two floors of the building are divided into seven equal modules divided by pilasters. In the central module of the first floor there is a simple lintel doorway. Right above it, already on the second floor, is sculpted the emblem of the Cathedral Chapter, the Giralda between two jars of lilies. Above the emblem is a simple oculus that serves to distinguish this central module, since in all the others rectangular windows framed by simple stone moldings open.

The old Cilla del Cabildo was declared a Site of Cultural Interest in 1985 and is currently home to the Reference Department, the Library, a conference room, the research room and other services of the General Archive of the Indies.