The Church of Our Lady of Consolation, generally known as "los Terceros", is a 17th century Baroque temple that stands on Calle Sol, in the Seville neighbourhood of Santa Catalina. Originally it was the church of the convent of the Third Order of Saint Francis that stood in this area and hence its popular name. It has a Latin cross plan, with a single nave and side chapels. It has only one façade on the outside, the one at the foot, which features an exuberant Baroque doorway. Since 1973 the church has been the headquarters of the Hermandad de la Cena, which processes on Palm Sunday.

History

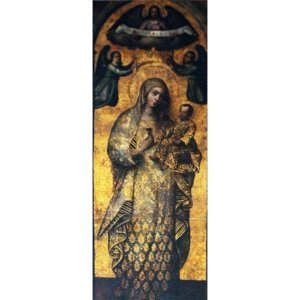

A group of Franciscan monks belonging to the Third Order moved to Seville from the now defunct convent of San Juan de Morañina, in Bollullos Par del Condado. After arriving in the city, they settled in this area, near an old hermitage dedicated to Saints Cosme and Damián. From their previous convent in Bollullos, the monks brought an image of the Virgin of Consolation that was already greatly worshipped in its place of origin. The popularity of the image continued after its arrival in Seville, becoming the object of growing veneration among the locals. It seems that this was the seed for the construction of the convent and its church to begin in 1648, logically dedicated to the Virgin of Consolation.

The construction of the convent and its church continued until the 18th century and the Franciscans ran it until the French occupation in 1810, when the Napoleonic troops used it as a barracks and proceeded to plunder a large part of its heritage. The following year it was handed over to the Augustinian nuns and in 1819 the Franciscans returned. However, it would not last long, since in 1835 they abandoned it definitively as a consequence of the famous Mendizábal confiscation. A period of abandonment then began, the worst consequence of which was the collapse of the church vaults in 1845.

Image of the Virgin of Consolation, formerly the Virgin of Morañina. Image from the article by Adrián Bizcocho Olarte on “Popular religiosity...”

A new episode in the history of this convent began in 1888 when the Piarist Fathers took charge of it, carrying out important educational work in the city. They managed it until 1973, when they moved to Montequinto. That same year, Cardinal Bueno Monreal gave the use of the convent church to the Hermandad de la Cena, which has since been responsible for its maintenance and has undertaken the various restorations that have been necessary, such as the renovation of the roofs in 1988.

The rest of the convent currently serves as the headquarters of EMASESA, the public company for the management of water in the city. The two cloisters, the main one and a secondary one, are preserved, as well as a majestic monumental staircase designed by Fray Manuel Ramos at the end of the 17th century.

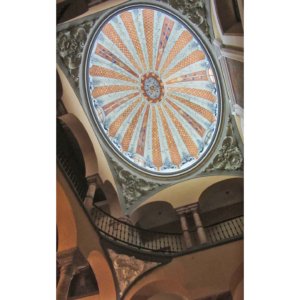

Former convent of the Terceros, today headquarters of EMASESA. Cloisters and dome over the staircase. Images from the blog Siglos de Sevilla.

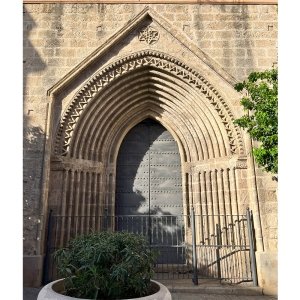

Outside

The church has only one façade, located at the foot of the temple, on Calle Sol. It has a very interesting doorway made at the beginning of the 18th century in a baroque style that is very reminiscent of the style developed at the same time in Hispanic America. The authorship of the design is unknown, although it has traditionally been attributed to Friar Manuel Ramos, the creator of the monumental staircase we mentioned when referring to the area of the convent.

The doorway is arranged like a three-lane altarpiece, with the central street occupied by the lintelled opening that is the entrance to the temple itself. The decoration was made using baked clay and exposed brick, with certain characteristics that, as we said, directly allude to Hispanic American baroque: the architectural elements take on curious and imaginative shapes and are filled with meticulous decoration that includes a multitude of symbolic elements.

On the side streets there are two niches with the terracotta carvings of Saint Joseph of Calasanz on the left and Saint Francis on the right. The two saints allude to the two main religious orders that have succeeded one another in the management of this temple since its creation: Saint Francis to the religious of the Third Order, founders of the convent, and Saint Joseph of Calasanz to the Piarists, who managed it from the end of the 19th century. This indicates that the sculptures are not the originals of the doorway, but were added much later, most likely already in the 20th century. In addition, their size is somewhat smaller than what would correspond to them according to the niches they occupy.

In the upper part of the side streets we find two medallions with the busts of two saints linked to the Franciscans, Saint Clara on the left and Saint Rose of Viterbo on the right. Above the door there is a space like a mixed-linear pediment in the centre of which there is a shield with Franciscan symbols. On the top left are the Five Wounds, the main symbol of the order, and on the right are three fleurs-de-lis. On the bottom, a hand points to a sun on which can be read "FIDEI" (Faith). Above the shield, an open royal crown at the base of which can be read "POENITENTIA CORONAT". We have no further information about the shield, although it must have been the one adopted by this convent as its own. In 2007 the Andalusian Institute of Historical Heritage undertook the restoration of a processional banner found in San Telmo with the same shield, so in all probability it was a banner representing the convent at official events.

On the four pillars that delimit the streets of the doorway are four Franciscan saints: on the left, Saint Anthony of Padua and Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, and on the right, Saint Elizabeth of Portugal and Saint Ivo of Kermartin, patron saint of lawyers. Crowning the central part of the doorway, a niche houses an image of the Virgin of Consolation, reproducing the original carving found inside. Above the Virgin appears a white dove with open wings, representing the Holy Spirit, and crowning the whole is a carving of Saint Michael.

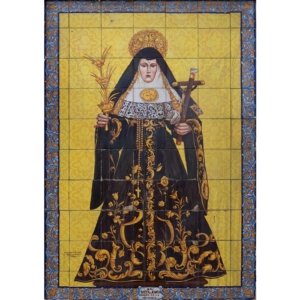

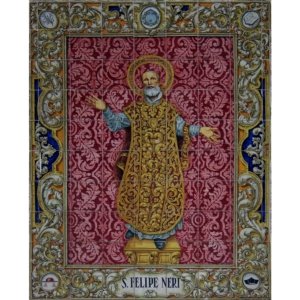

To the right of the doorway is a ceramic altarpiece with the image of the Virgin of the Underground, the Marian patron of the Brotherhood of the Supper. It was made in 1959 in the factory of Nuestra Señora de la Piedad by Antonio Morilla Galea and Manuel García Ramírez.

The façade has a tower on the right, topped by a two-body belfry with two openings for bells in the lower one and a single body in the upper one, topped by a curved pediment.

Inside

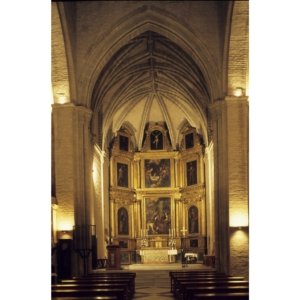

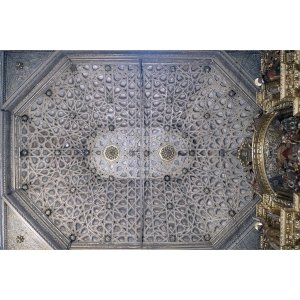

The first thing that catches your attention when you enter the Consolación church is its large size and monumentality, making it one of the most interesting examples of the convent churches of the Sevillian Baroque. It consists of a single nave of great width and in the shape of a Latin cross. On either side of the nave there are a series of side chapels which are accessed through semicircular arches closed by bars. At the foot of the church is the high choir, resting on a profusely decorated segmental vault. On one side of the choir is an organ, original from the first half of the 18th century, which according to Álvaro Cabezas García can be attributed to the altarpiece maker José Fernando de Medinilla. The original roof of the church was made by a large barrel vault that extended throughout the nave. However, this vault collapsed in the mid-19th century and today we find a flat roof. The barrel vault is preserved only over the choir, at the foot of the church, and over the presbytery area, at the head. Above the transept there is a hemispherical dome on pendentives, decorated with plasterwork that reproduces architectural elements, plant decoration, scrolls, angels' heads and other motifs characteristic of the Baroque.

This type of decoration based on plasterwork must have originally extended throughout the vault of the church. The decoration of the vault that supports the choir is especially rich, and in it the curious bunches of various fruits stand out, in a composition articulated by latticework and plant motifs, in which little angels and Marian symbols are mixed. It clearly recalls the plasterwork that we find in Santa María la Blanca, also made in the 18th century.

Presbytery

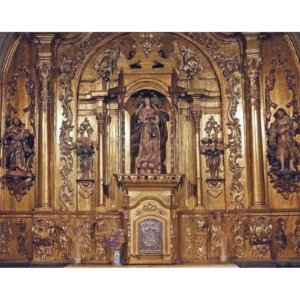

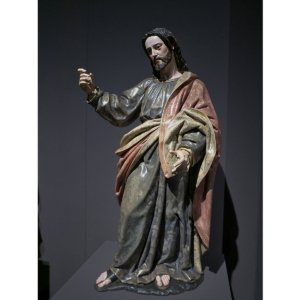

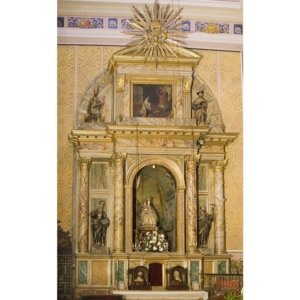

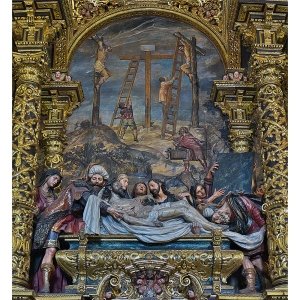

In the presbytery, the main altarpiece is a splendid baroque ensemble made by Francisco Dionisio de Ribas in 1669, which was subsequently renovated on several occasions. It can be considered one of the best examples of 17th century Sevillian altarpieces. It consists of two bodies and three sections, delimited by beautiful Solomonic columns with shafts delicately sculpted with plant motifs. The layout of the central space of the altarpiece was modified to accommodate the sculptural group of the Last Supper after the brotherhood was established in this temple. In the centre appears the figure of Jesus at the moment of the Eucharistic celebration. It was carved by Sebastián Santos Rojas in 1955 and its face is of such beauty that there are authors who point to it as the most beautiful image of Christ among those made for Holy Week in Seville in the 20th century. The apostles are the work of the Cadiz sculptor Luis Ortega Bru, one of the most original and outstanding figures of contemporary Spanish imagery. They were his last work, as they were first performed during Holy Week in 1983, a year after the sculptor's death. When the group is in the altarpiece, only eleven apostles accompany the Lord, as Judas Iscariot is excluded, who is part of the float on the day of the procession.

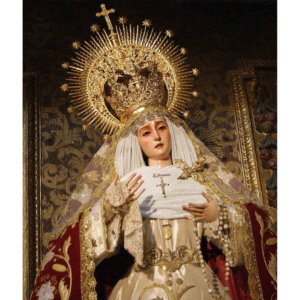

Above the group of the Last Supper, there is a niche with undulating shapes added to the altarpiece in 1700 to house the Virgin of Consolation, the titular of this temple. It is a small image of the Virgin with Child, which originally had the title of Our Lady of Morañina when it was worshipped in the convent that the Third Order ran in Bollullos Par del Condado before its transfer to Seville. The image dates back to the 14th century, but was thoroughly renovated to adapt it to the Baroque aesthetic, probably in the 18th century.

Continuing along the first level, on the left we find Saint Ivo of Brittany and Saint Elizario, while on the right we find Saint Conrad and Saint Louis of France. In the second level, in the centre there is a relief with "Saint Francis approving the rules of the Third Order". The relief is flanked by Saint Elizabeth of Portugal on the left and Saint Elizabeth of Hungary on the right.

Transept

The presbytery is flanked by two other smaller altarpieces located in the arms of the transept. Both are from the first third of the 18th century and house an image of the Virgin and Child on the left and a Jesus of Nazareth on the right. Originally the altarpieces were dedicated to two high-quality images of Saint Michael and Saint Raphael that are currently usually located in the sacramental chapel.

At the left end of the transept there is an altarpiece from the beginning of the 18th century that houses the image of Our Lady of the Underground, Queen of Heaven and Earth, titular of the Brotherhood of the Supper. The image is a painful one to dress that has traditionally been attributed to the 19th century sculptor Juan de Astorga, although due to its stylistic features it cannot be ruled out that it is an older image, probably from the 17th century. The altarpiece in which it is located once belonged to the Brotherhood of Love, which had its headquarters in this church. In fact, behind the Virgin, the shape of the cross that once housed the Christ of Love is visible. It is worth remembering that the Brotherhood of the Holy Entry into Jerusalem was also founded in this church and that it was here that both merged to give way to the Brotherhood of Love that we know today, based in the church of El Salvador. In fact, in the attic of the altarpiece there is a relief that represents precisely the scene of the Entry of Jesus into Jerusalem, riding the famous "little donkey".

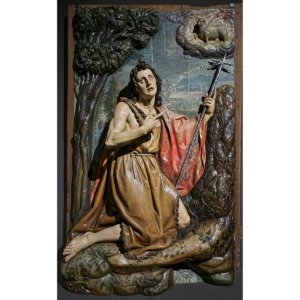

Opposite the altarpiece of the Virgin of the Underground, in the right-hand head of the transept, there is an altarpiece with very dynamic shapes carved by Fernando de Medinilla in 1727. It is presided over by the image of the Christ of Humility and Patience, which is also the titular of the Brotherhood of the Supper, also participating in the procession on its float. The image was made in the 16th century, making it one of the oldest images of Holy Week in Seville. It has the peculiarity of not being made of wood but of glued fabrics. It represents Christ sitting on a rock just before the crucifixion, resting his head on his right hand in a reflective attitude. This iconography has deep roots in Sevillian religiousness since the first carvings were made from an engraving by Dürer in 1511.

Chapels

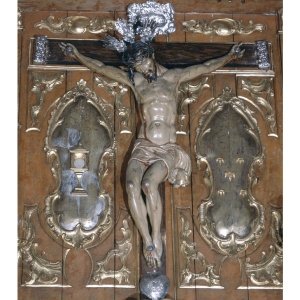

On the Gospel side (left) of the church is the Sacramental Chapel, with a rectangular floor plan and a barrel vault with lunettes. Both the walls and the vaults are profusely decorated with baroque ornamentation from the beginning of the 18th century. It is presided over by a neoclassical altarpiece from the 19th century presided over by an Immaculate Conception. It is flanked by carvings of Saint Mary of Egypt and Saint Anthony of Padua, and in the attic there is a Crucifix. All the carvings are approximately from the beginning of the 19th century, except for the Immaculate Conception, which is from the 17th century. On both sides of the chapel are two altarpieces, also neoclassical, which house the images of Saint Michael and Saint Raphael from the beginning of the 18th century. Also in this chapel is a dressed image of Saint Francis from the 17th century that apparently came out in procession through the streets of the neighbourhood. There is also a crucifix with the dedication of Christ of the Good Death, of remarkable quality, which has been dated to the beginning of the 18th century.

Opposite the sacramental chapel, on the Epistle side (right) is the chapel of Our Lady of the Incarnation. It is presided over by a neoclassical altarpiece that houses the image of the Virgin who is the titular glory of the Brotherhood of the Supper. It is a 17th century carving attributed to Juan de Mesa, although it was deeply renovated later. The chapel remained closed for a long time after suffering a collapse but can be returned to worship after its restoration in 2019.