The Church of the Divine Savior of Seville is the second largest temple in the city, only after the Cathedral. It is one of the great architectural jewels of the city and inside it houses a magnificent sculpture collection, with works by the most prominent authors of the Sevillian baroque. As a result of its long and complex history, a huge and majestic temple with three naves has been created. The transept stands out noticeably in height over the rest, although it is not perceptible in the floor plan of the building, which is called a living room.

History

We know that in the space it occupies today was the so-called mosque of Ibn Adabbas, created around 830 as the aljama or main mosque of the city. It held this rank until the new great mosque was built in the 12th century, on the site now occupied by the Cathedral.

Some elements of the mosque that was located in El Salvador have been preserved, such as part of its patio and the beginning of its minaret, which corresponds to the lower part of the tower that we find at the northern end, on Córdoba Street.

Once the city was conquered by the Christians in 1248, the mosque was used as a church, although maintaining the essentials of its structure. It remained this way for centuries, with the architectural characteristics of an Islamic temple but serving for Christian worship, as continues to happen today, for example, with the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba.

However, when the 17th century arrived, it seems that its condition was quite ruinous and it was decided to build a new temple. Work began around 1674, but when the vaults were being closed, a resounding collapse occurred that forced a good part of the project to be rethought.

Leonardo de Figueroa, the best architect of the Sevillian baroque, who also intervened in other projects such as San Luis de los Franceses or La Magdalena, was eventually entrusted with directing the works. In this case, Figueroa was in charge of closing the vaults, building the large dome and finishing the interior of the building. The works were not completed until 1712.

Outside

Courtyard and Tower

Today you can see some remains of the old mosque in the current Patio de los Naranjos, where some of the columns that surrounded the primitive ablution patio are preserved in situ. Some of them have Roman and Visigoth origin, and their depth makes it clear that the height of the mosque was much lower than that of the current church.

The base of the bell tower, between the patio and Córdoba Street, was also the original minaret of the mosque, completely altered on its upper floors by successive renovations. The upper part that we can see today was added by Leonardo de Figueroa at the end of the 17th century.

Capilla de los Desamparados

At the western end of the patio is the Chapel of Cristo de los Desamparados, a small rectangular temple that was built in the mid-18th century, under the direction of one of Leonardo Figueroa's sons, Matías or Ambrosio. Sources differ in this regard.

The interior is covered by two elliptical vaults, the one closest to the main altar being crowned by a lantern. Its walls are profusely decorated with baroque mural paintings and a series of niches open on the sides as side altars. In one of them is located the Virgen del Prado, a dress image made by the image maker Sebastián Santos in 1949, who is the owner of his own brotherhood of glory.

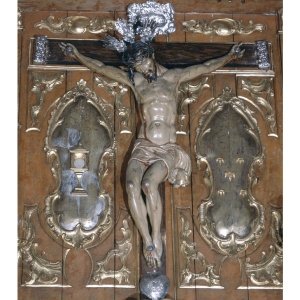

The main altarpiece is occupied by the image of the Cristo de los Desamparados, owner of the chapel, a crucified by an anonymous author that has been dating back to the 16th century.

Church Facade

As for the church itself, the main façade has very classic baroque lines and Italian influence, close to Renaissance forms. The succession of stone pilasters and reddish brick panels achieve the classic bichrome that is so characteristic of many Sevillian buildings since the Lonja, today the Archive of the Indies, was built in the 16th century.

Despite its monumentality, the Salvador façade stands out for its scarce decoration, which contrasts greatly with the interior.

It is organized into three streets separated by pairs of pilasters, which correspond to the three naves of the temple. In the first body there are three doors, with the central one larger than the side ones. They are framed in a very classic way, with pilasters supporting a lintel on which a second, much smaller body opens. Two angels on each lintel hold a shield with the representation of the "Agnus Dei". On the main portal, a globe crowned by a cross symbolizes the "Savior", while the side portals are crowned by the effigies of Saint Peter and Saint Paul.

The Plateresque-style decoration that runs through the pilasters and some of the moldings is relatively recent, from the end of the 19th century. Two oculi framed by square molding open on the side portals.

In the second body, we find only the extension of the central street, framed again by pilasters, and with a large central oculus as the only decoration. On each side, there are two areas decorated with scrolls, very frequent elements in European religious architecture since the Renaissance. They have the function of softening the transition between the great width of the first body and the much smaller width of the second.

Behind these convoluted spaces are hidden two buttresses that seem to serve to support the weight of the walls of the central nave. It should be noted that these elements are traditionally linked to Gothic architecture and not to Baroque. In the case of El Salvador they are especially interesting since they apparently do not fulfill any structural function due to their position. It has been pointed out by several authors that the inclusion of buttresses would simply be due to a symbolic interest, that of highlighting the importance of the church as a collegiate temple by introducing this type of elements traditionally linked to a type of "cathedral" architecture. This is how José María Medianero Hernández explains it in an article dedicated to the survival of flying buttresses in Lower Andalusian architecture:

“The general compositional role does not appear to be fortunate given its setback composition with respect to the aforementioned lateral additions ending in volutes and its only functionality seems to be established in the mission of conducting the discharge of water. Of course, this trivial problem could have been solved in a simpler way. Perhaps the most plausible explanation is the recurrence to an emblematic motif of a collegiate temple with cathedral aspirations, desires and pretensions that architecturally transcend the packaging and elegance of the building.

Dome

The dome is the most recognizable element of the church of El Salvador, especially when the temple is viewed from a distance. It was built in 1709-1710 following the design and direction of Leonardo de Figueroa, an architect who created other masterful domes in Seville, among which those of the Magdalena and San Luis de los Franceses stand out.

In the case of El Salvador, it is a hemispherical dome on an octagonal drum. It has a height of more than 40 meters and a width of more than 10 meters. The elevated drum serves to highlight the dome above the rest of the church's roofs and eight windows open on its sides, crowned by alternating curved and straight pediments.

The domes of the church of El Escorial and the Clerecía of Salamanca have been noted as antecedents, both indebted to the dome designed by Bernini for the church of Castelgandolfo.

Inside

The church has a rectangular or hall floor plan, as it does not form the classic Latin cross shape so common in Christian churches. It is divided into three naves, the central one being higher and wider than the side ones. Although the church does not have side chapels, but rather altars, some spaces are attached to the main body of the floor, such as the old baptismal chapel, the sacramental chapel and the sacristy.

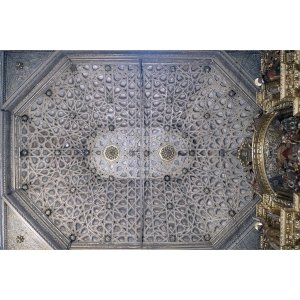

The vaults are supported by colossal square pillars to which are attached columns of composite order and richly sculpted shafts. The roof is made with a barrel vault in the central nave and the transept, and a groin vault in the side naves.

The sculptural decoration runs through the stone parts of the interior of the temple, such as the shafts of the columns or the spandrels of the arches. It is mostly plant decoration, scrolls and other baroque motifs. We also frequently see the royal coat of arms, especially in the keystones of the transverse arches, an element that had the purpose of emphasizing to the Cathedral chapter the fact that the church was a royally founded collegiate church. We also find decoration in the pendentives that support the dome, in which the busts of the four evangelists are located in medallions surrounded by profuse ornamentation.

Main Altarpiece

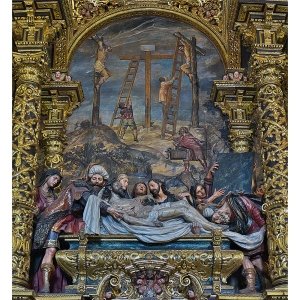

The church is dominated by an imposing baroque altarpiece, made between 1770 and 1779 by the Portuguese sculptor Cayetano de Acosta. It is a masterpiece of Sevillian altarpiece art that has sometimes been called "the last great altarpiece of the Spanish Baroque." The decorative profusion makes it difficult to distinguish the architectural structure of the altarpiece. In its center the scene of the Transfiguration of the Lord is represented, the moment in which Christ is present after the Resurrection on Mount Tabor. He is accompanied by Moses and Elijah, as representatives of the Old Testament and, on a lower level, the apostles Peter, James and John prostrate themselves in admiration. The central figure of Christ adopts a posture that has been related to the colossal Longinus that Bernini sculpted for St. Peter in the Vatican and is framed by a large scallop. The rest of the altarpiece is motley with countless figures of cherubs, angels and archangels. On the bench there are reliefs with representations of the Fathers of the Church and in the center we find a Tabernacle-Manifestator, crowned by an Immaculate Conception. In the attic, the figure of God the Father presides over the entire complex, emphasized by large golden sparkles behind him.

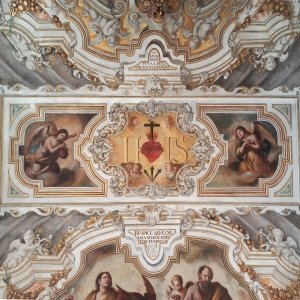

The hemispherical vault over the presbytery is decorated by tempera paintings that Juan de Espinal made at the end of the 18th century. It represents heavenly glory, with the Holy Spirit in the center, and through optical effects such as a fake balustrade, it manages to give the impression that it is a higher vault than it really is.

Organ

Above the main entrance to the church, there is today an imposing wooden organ, made by Juan de Bono and Manuel Barrera at the end of the 18th century. This organ was located in the center of the temple, in the choir area that opened in front of the High Altar. Collegiate churches were required to have their own choir, as is the case with cathedrals. A brilliant musical career developed in this temple since the 16th century, with such outstanding figures as the organist Correa de Arauxo, called "the Spanish Bach." In 1861 the collegiate character of the church was removed, the choir area was eliminated and the organ was moved to its current location. Even today, it is considered one of the best organs in Andalusia and is immersed in a restoration process.

Also magnificent is the altarpiece of the Virgin of the Waters, on the right side of the transept, a work by José Maestre from 1731 presided over by this Marian image of the so-called “fernandinas”, dating back to the 13th century but much remodeled later. These are just two examples of the large collection of altarpieces that this church houses.

And the representation in the temple of great masters of sculpture is exceptional. In all probability, the two great figures of the Sevillian baroque are Juan Martínez Montañés and his disciple Juan de Mesa.

Of the first, El Salvador preserves a colossal sculpture of Saint Christopher, reminiscent of Michelangelo for its monumentality and beauty. But the most outstanding work of this author in El Salvador is surely Our Father Jesus of the Passion, a moving image of the Lord with the cross on his back, which wonderfully shows the classicism of Montañés's baroque, managing to convey all the feeling and the emotion of the moment, but in a contained, elegant and solemn way. It presides over the silver altarpiece of the Sacramental Chapel and goes out in procession every Holy Thursday. We are not exaggerating when we say that it is one of the most successful representations of Jesus the Nazareth of the Spanish Baroque.

From the other great master of Sevillian baroque, Juan de Mesa, we find the Christ of Love, who also processions from this temple during Holy Week, this time during Palm Sunday. It is an exceptional carving of a crucified man, already dead, with a masterful treatment of the anatomy, hair and cloth. An exceptional work within the production of its author, which seems to have taken into account for its creation the model that his teacher Montañés made a few years before with the Christ of Clemency that we found in the Cathedral.

Along with these masters, the list of great artists with works in this church of the Savior is almost countless. We could cite, for example, Duque Cornejo, José Montes de Oca or Antonio Quirós. But for now we finish here this small sketch about the authentic living museum of Sevillian baroque that is the old schoolhouse of El Salvador. We will tell more in future installments.

And remember that if you are interested in taking a guided tour so as not to miss any of the details, you can contact us by any means you prefer from this website.