The church of San Alberto is the temple of the convent of the same name, which currently houses the Congregation of the Oratory of San Felipe Neri (Philippian fathers). It is a church with a single nave built in the first half of the 17th century, but with profound reforms in the following centuries.

History

The convent originally belonged to the order of the Carmelites, who founded the convent of San Alberto in 1602 as a center of higher education. The church was not consecrated until 1626 and work continued for a few more years, with the completion of the main chapel in 1640.

The convent and the church suffered considerably during the French occupation (1810-1812), when the complex was transformed into a barracks for Napoleonic troops. A good part of its artistic heritage was then lost.

After the war, the Carmelites would return to the convent, although it would not be for long. After the Confiscation of Mendizábal (1636) they were forced to abandon it. From that moment on, it went through various uses, such as the headquarters of the Royal Academy of Good Letters or a secondary school. Finally, it was acquired by the Philippian fathers at the end of the 19th century.

A dispute then began with the Carmelites, former owners of the property, who defended their right to return to it. Finally, through the intermediation of Cardinal Spínola, the Carmelites settled in the old Buen Suceso hospital, where they remain today. To seal the peace, the Philippians had to give them some artistic works of special relevance that were originally in this church and that are today found in Buen Suceso. We can cite the magnificent “Saint Anne presenting the Virgin in the Temple”, by Martínez Montañés, or the carvings of “Saint Albert” and “Saint Teresa”, by Alonso Cano.

Description

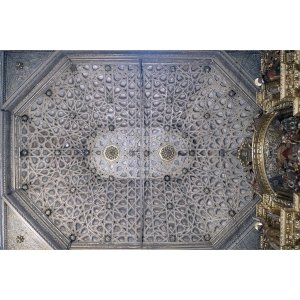

The church responds to a late-mannerist model that we found on other occasions in Seville. It has a rectangular floor plan and a single, large nave. It is divided into five sections by large buttresses. Between them a series of side chapels-niches open, over which a tribune runs.

The covering is done by lowered vaults with lunettes and transverse arches. Especially interesting is the elliptical dome that covers the transept. It sits on pendentives and eight oculi open in it, giving it luminosity.

The presbytery is slightly elevated with respect to the rest of the church and at the foot of the temple is the high choir, also sitting on a lowered vault with lunettes.

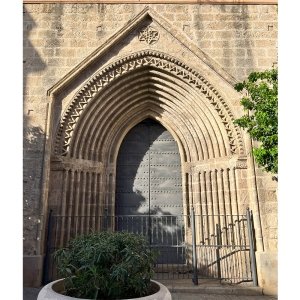

Outside

Access to the church is through a simple mannerist door open at the foot of the right wall. It is a work with very simple lines that has been related to the architect Diego López Bueno. Above the door there is a split pediment with a niche in the center. The sculpture represents Saint Albert and was carved in 1626 by Alonso Álvares de Albarrán, a disciple of Martínez Montañés. It has some remains of polychrome, but it probably comes from some restoration in the 19th century.

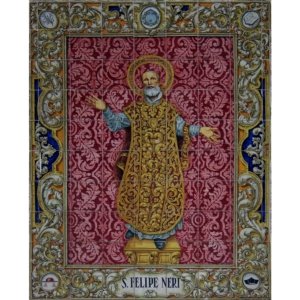

In a curious chamfer on the left side of the façade there is an open chapel with two sections. The first and largest is dedicated to the Virgin of Carmen, while the upper one houses a tile of the Virgin of Perpetual Help. To the right of the doorway we find another ceramic altarpiece, this time reproducing the carving of San Felipe Neri that is found inside the church. Fernando Orce painted it for the Pedro Navia factory in Triana around 1955.

Although it is difficult to see from the façade, the church has a bell tower visible from the surrounding streets. It presents the usual tile decoration of the Sevillian bell towers and is dated 1739. It is very likely that the tower is earlier and that this date corresponds to a major renovation that had to be undertaken after it was badly damaged in 1736 when it fell on it. a ray.

Inside

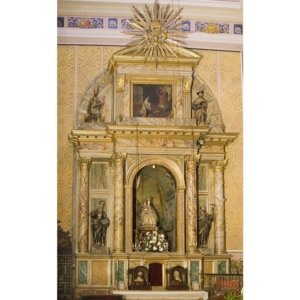

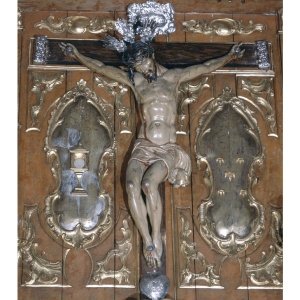

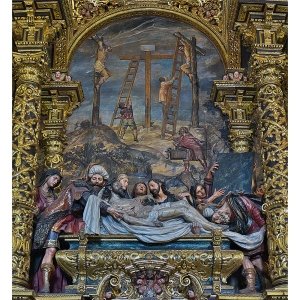

The main altarpiece is neoclassical in style and was made to replace a previous baroque style altarpiece destroyed during the French occupation. In its large central niche, there is a Crucified figure that reproduces the Christ of Clemency by Martínez Montañés. It was made in 1791 by a sculptor named Ángel Iglesias, of whom no other works are known.

At the foot of the Cross there is an anonymous 18th century Dolorosa dress. It is of notable quality and it has been pointed out that it could be the painful primitive of the Brotherhood of the True Cross (Manuel Jesús Roldán, “Iglesias de Sevilla”).

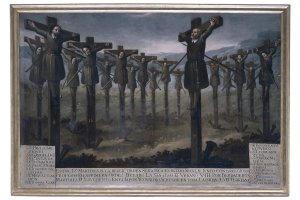

In the side streets are Santa María Magdalena and Santa María Egipciaca, interesting works by Duque Cornejo (18th century). In the attic we find anonymous sculptures dating from the same period as the altarpiece. In the center, a group represents “The Apotheosis of Saint Albert”, and on the sides are Saint Elias and Saint Teresa.

In the presbytery area, the lamp angels are also interesting, made in the 18th century by Cayetano de Acosta, one of the most prominent sculptors of this century in Seville.

The rest of the altarpieces are neoclassical, from the 19th century, and are not of considerable quality. Some of them can be mentioned because they have some aspect of interest:

- Altarpiece of the Virgin of Valvanera. In its central niche it houses an interesting image from the early 19th century that reproduces the Virgin of Valvanera, patron saint of La Rioja. It is flanked on the side streets by Blesseds Antonio Gassi and Juan de Ávila. In the attic there is a painting with "The Breastfeeding of Saint Bernard", anonymous from the 18th century, which reflects the medieval tradition according to which the Virgin Mary appeared to the saint to grant him the gift of eloquence by giving him to drink her own breast milk. she. On both sides are two saints, presumably Carmelites, but not identified.

- Altarpiece of San José. Located next to the previous one on the left side of the church. The only notable thing is the central carving that represents Saint Joseph with the baby Jesus in his arms. Saint Joseph has traditionally been one of the favorite devotions of the Carmelites. Here we find it in a carving made by the Sevillian sculptor Cristóbal Ramos around 1782. It is worth highlighting the moving delicacy with which Saint Joseph rests his cheek on the head of the Child.

- Altarpiece of San Antonio. It is located in one of the niches on the Gospel side (left). The altarpiece and the central carving do not present much interest from an artistic point of view, but the five paintings that decorate it are worth highlighting. They represent the Four Evangelists in the side streets and “The Coronation of the Virgin” in the attic. Historically they were attributed to Francisco Pacheco, but today they are considered works of Juan del Castillo from around 1632.

- Altarpiece of San Felipe Neri. Located on the right side of the transept, in front of the altarpiece of the Virgin of Valvanera. Its interest lies in the carving of the saint that occupies the central niche. It is a work of great quality that was sometimes linked to the production of Pedro Roldán. Today it is considered more of a work by Duque Cornejo, based on an attribution made by Manuel García Luque, which dates it to the beginning of the 18th century.

- Nativity altarpiece. It is located next to that of San Felipe Neri, on the Epistle side. Of particular note is the sculptural ensemble of the Nativity located in the central niche, dating back to the 18th century. On the sides are San Joaquín and Santa Ana. Both appear to be from the 17th century, although apparently they were not made together, since the figure of San Joaquín is somewhat smaller.

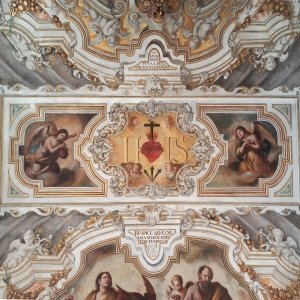

The rest of the altarpieces are interesting for their devotional value rather than their artistic value. They are dedicated to such popular devotions as the Sacred Heart, the Virgin of Perpetual Help or Saint Joseph.

º : Repositorio Gráfico IAPH │ * : Leyendas de Sevilla