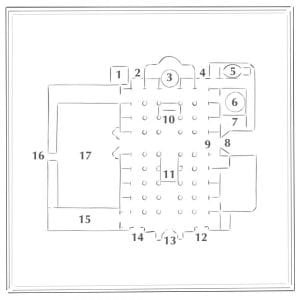

The church of the convent of Santa María de Jesús is the only currently visitable part of a monastic complex of Poor Clare sisters that has been located on Águilas Street since the 16th century. It is a classic “box church” ("iglesia de cajón"), so common in Sevillian convents, which is why it has a rectangular floor plan and a single nave.

History

The convent of Franciscan nuns of Santa María de Jesús was founded in 1502 by Jorge Alberto de Portugal and his wife, Filipa de Melo, who eventually became the first counts of Gelves by concession of Charles V. Since its origin it has been a convent of barefoot nuns of the First Rule of Saint Clare (Franciscan). The construction of the current church was undertaken at the end of the 16th century and was considerably renovated at the end of the 17th century and in the middle of the 19th century.

Another important milestone in the history of this church would be the disappearance in 1996 of the Sevillian Convento de Santa Clara, on Becas Street. The few nuns who remained in the cloister moved to this convent of Santa María de Jesús, bringing with them some of the movable property belonging to the old convent.

Outside

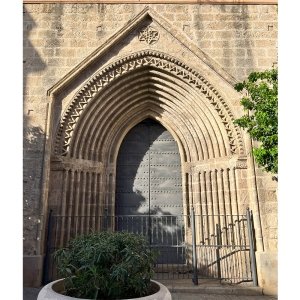

Access from the outside is through a Mannerist doorway open on the left wall, in whose design the architects Juan de Oviedo and Alonso de Vandelvira are known to have participated. It is a lintelled doorway, framed by classic Ionic style pilasters and topped by a split and curved pediment. Above the center is a niche, topped this time by a triangular pediment, which houses a beautiful seated sculpture of the Virgin holding the Child Jesus. On the lintel above the door, two angels hold an inscription that reads "Sancta María ora pro nobis", in which "María" has been replaced by the symbol of the Ave Maria (AM). Just below appears "SE REN. YEAR OF 1695", referring to the date of one of the most important reforms undertaken in the temple.

A few meters to the right of this doorway, you can see another one that is now blocked off and which was once the primitive access to the cloister. In the center of this old entrance there is currently a ceramic altarpiece of San Pancracio that is very popular among Sevillians. It was made in the 40s of the 20th century by Alfonso Chaves Tejada at the Ramos Rejano Factory in Triana.

Inside

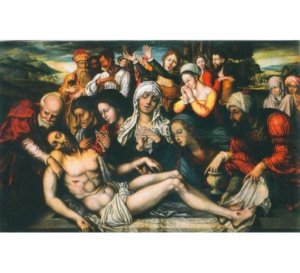

Inside, the nave is covered by a barrel vault with lunettes and transverse arches. Intricate plasterwork decorates the base of the transverse arches, the center of the vaults and the semicircular space under the lunettes. In this area, the plasterwork frames the windows that open onto the street on the Gospel side and a series of canvases from the old convent of Santa Clara on the Epistle side.

At the foot of the church, there are the upper and lower choirs, reserved for the cloister and separated from the rest of the temple by a wall in which large bars and two side doors open.

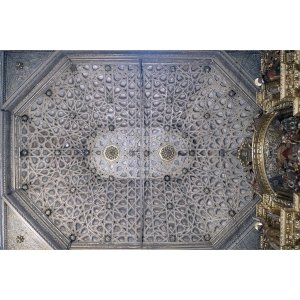

A large main arch on marble columns separates the nave from the presbytery like a triumphal arch. In its lower part, a small fence makes the presbytery an exclusive area for the officiants and the nuns. It is covered by a splendid eight-panel coffered ceiling in the Mudejar style, dating from the end of the 16th century. This characteristic is quite particular to this church, since in general in Sevillian convent churches it is common to cover this area with Gothic-style stone vaults. It has a tile plinth dated 1589 and attributed to the ceramist Alonso García. The walls are profusely decorated with baroque motifs and little angels that frame representations of archangels and allegories of monastic life. They have been dated to the end of the 17th century and their state of conservation is quite poor.

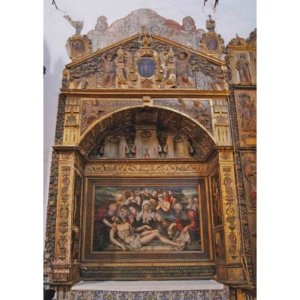

The main altarpiece was also made at the end of the 17th century and is of extraordinary quality. Cristóbal de Guadix was its assembler and Pedro Roldán the image maker, making all the sculptures, with the exception of the Virgin who occupies the central niche that is later. The central body is divided into three streets through four splendid Solomonic columns. On the left we find Saint Francis and, above him, a bust of Saint Michael. In parallel, on the right is Santa Clara and a bust of Santa Catalina. It should be remembered that Saint Francis is obviously the founder of the order that bears his name and Saint Clare the architect of its female branch.

The central street is almost entirely occupied by a large niche that houses a beautiful seated image of the Virgin changing the diapers of the Baby Jesus. Although it lacks reliable documentation, this image has been attributed to Luisa Roldán, la Roldana, based on her stylistic characteristics. Above the niche, a small temple houses a representation of the Eucharist.

In the center of the attic, a high relief represents the Nativity of the Virgin, framed in curious architectural forms that emphasize the sensation of depth of the composition. On both sides, the figures of the "Santos Juanes", San Juan Bautista and San Juan Evangelista, always present in the Sevillian conventual churches.

Also inside the presbytery, to the right, is a small altarpiece, framed by Solomonic columns, dedicated to the Jesus of Forgiveness. It is a representation of Jesus with the Cross on his back, from the 17th century and in full size, something quite unusual for the Sevillian Nazarenes. Its authorship is not documented but it has sometimes been attributed to Juan de Mesa himself, author of Gran Poder. In the attic of the altarpiece we find a relief in which Pope Honorius III is represented giving Saint Francis the Rules of the Order.

Although the temple does not have side chapels, several altarpieces are attached to its walls as small altars. On the Gospel side, we find two dated to the end of the 17th century and also attributed to Cristóbal de Guadix. They are dedicated respectively to Saint Anne, who appears in the traditional attitude of teaching the Virgin to read, and to Saint Andrew, holding the cross in the shape of a cross on which he was martyred.

On the opposite wall, the first altarpiece is dedicated to Saint Anthony and is of similar chronology and characteristics to the previous ones. Something later seems to be the next altarpiece, dedicated to the Immaculate Conception, which is presided over by a beautiful carving from the 18th century that has been attributed to both Duque Cornejo and Luisa Roldán.

The next altarpiece, just in front of the entrance, is from the 20th century and houses a also modern image of Saint Pancras. It is probably the image with the least artistic value in the church but one of the ones that arouses the most popular fervor, since popular religiosity has been attributing to Saint Pancras the ability to effectively mediate especially in matters related to the work and economic sphere.

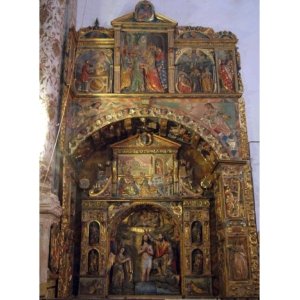

Finally, next to the low choir, the oldest altarpiece in the temple is located. Of Renaissance style, it dates back to 1587 and is the work of Asensio de Maeda and Juan de Oviedo. In the central body, framed by two Ionic columns, there is the relief of Jesus on the way to Calvary, which has the particularity that the Cross is held in a different way than usual, with Christ embracing the longest section, just like the does Our Father Jesus of the Brotherhood of Silence. In the attic there is another relief representing God the Father, probably also from the end of the 16th century, and on the bench we find a painting with the "Souls of Purgatory", already from the 18th century.

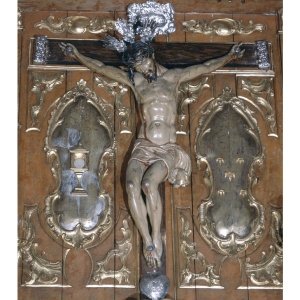

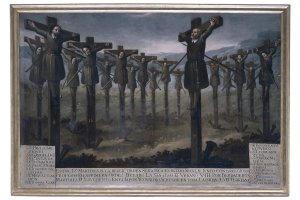

In the center of the wall that separates the nave from the upper and lower choirs, there is a Crucified Christ from the 17th century from the exclaustrated Convent of Santa Clara. It is located in the center of a curious canopy in which the emblems of San Francisco and Santa Clara (Franciscans) can be distinguished. On both sides there are two canvases also from the 17th century with "The Franciscan Martyrs of Japan" and "The Foundation of the Third Order by Saint Francis." In both there are signs with descriptions at the bottom, making their didactic purpose clear.

* Repositorio Gráfico del IAPH : https://repositorio.iaph.es/