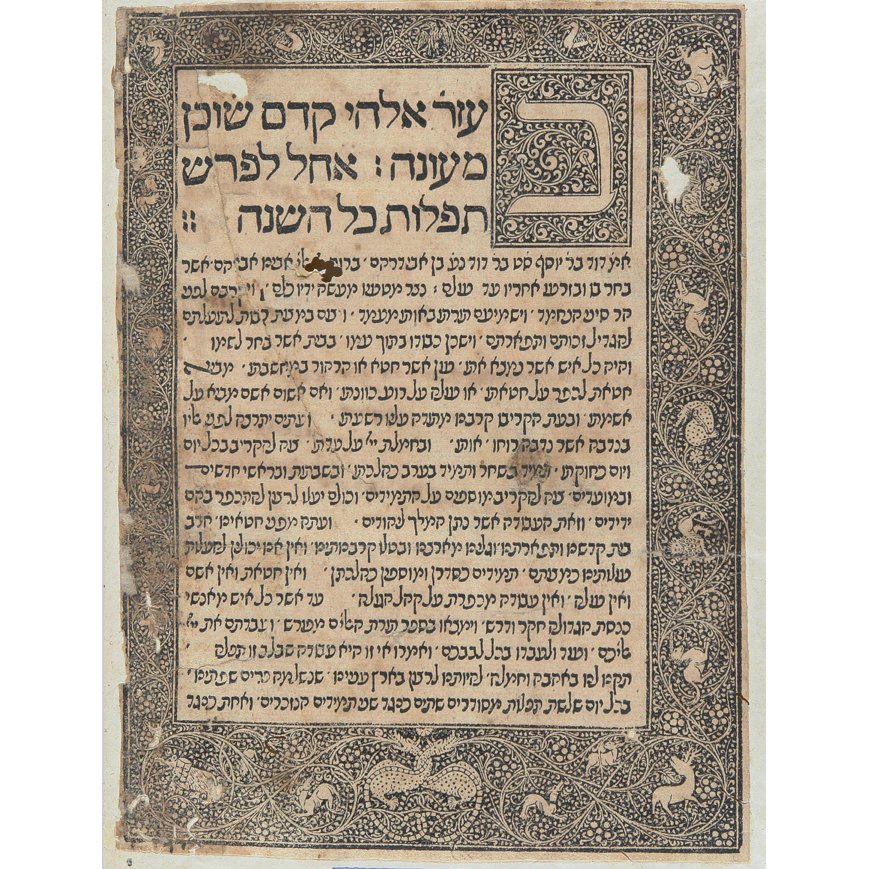

JUDAH IBN VERGA

(15th century)

His name is also transcribed as Yehudá Ibn Verga. He was a Jewish mathematician, astronomer and Kabbalist born in Seville. It is known that he was a relative of Salomón ibn Verga (probably his uncle), author of the "Shebeṭ Yehudah" ("The Staff of Yehudah"), and it is this work that provides some details of Ibn Verga's life.

On one occasion he came to the defense of a group of Jews from Jerez de la Frontera who were accused of moving the body of a converted Jew to their cemetery. Judah defended him against the Duke of Medina Sidonia, demonstrating through a Kabbalistic writing that the real criminals were the priests ("Shebeṭ Yehudah", 38). He was very active in maintaining an understanding between the converts and the Jews. When the Inquisition was established in Seville, he was pressured to abandon the Jewish faith, but he finally managed to flee to Lisbon, where he remained in hiding for several years. When the expulsion of the Jews from this country was decreed in 1497, Judah was imprisoned and tortured to make him betray the new Christians who continued to practice Judaism secretly. He died in prison as a result of this torture in 1499.

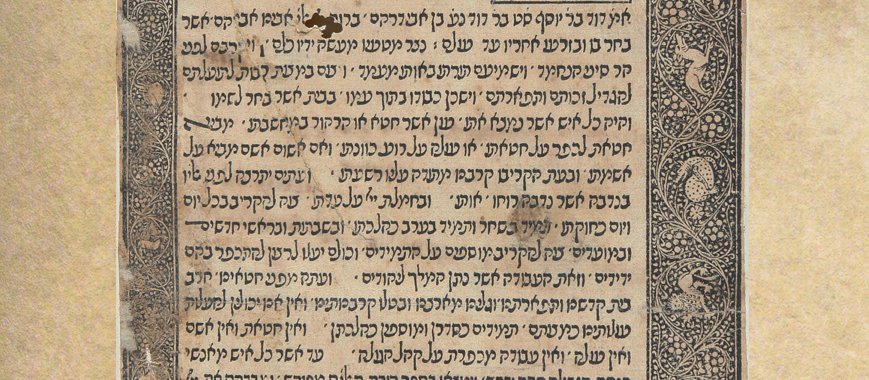

Ibn Verga wrote a history of the persecutions of the Jews, largely taken from the "Zikron ha-Shemadot" of Profiat Duran; this work is in turn the embryo from which the "Shebeṭ Yehudah" is written.

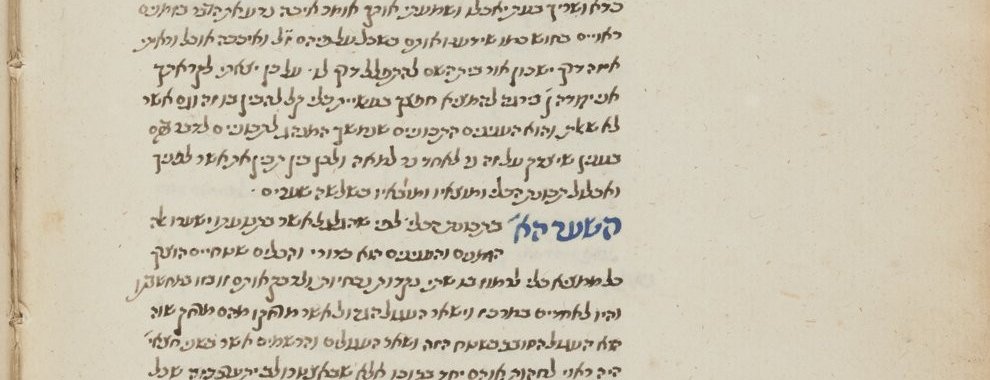

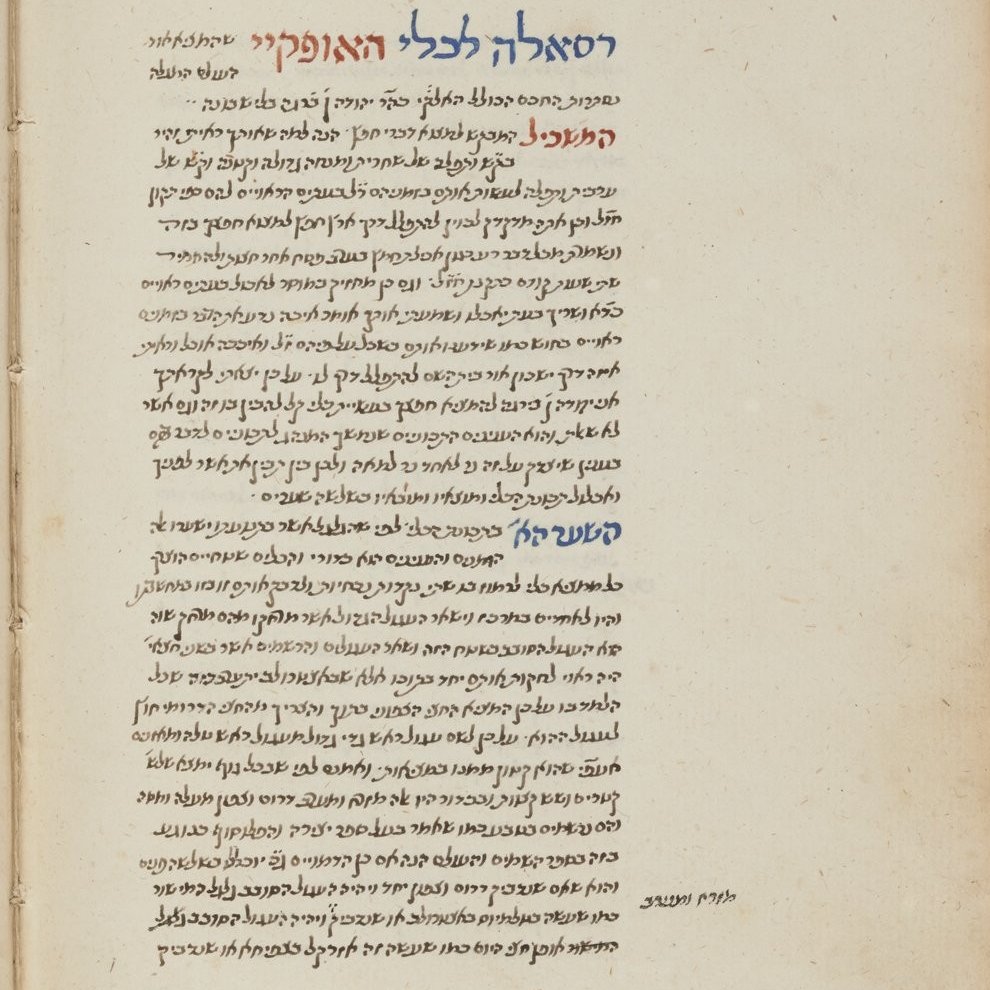

The Bibliothèque Nationale of Paris (MS. No. 1005, Hebr.), contains a series of scientific treatises written by one Judah ibn Verga, who is generally identified with the Judah ibn Verga of the "Shebeṭ Yehudah." If they were his works, they would make clear the great erudition and breadth of areas he covered. These treatises are:

- "Ḳiẓẓur ha-Mispar", a short manual of arithmetic (ib. folios 100-110a);

- "Keli ha-Ofeḳi", a description of the astronomical instrument he invented to determine the meridian of the sun, written in Lisbon around 1457 (folios 110b-118a);

- a method for determining altitudes (folios 118b-119b);

- a short treatise on astronomy, the result of his own observations, completed in Lisbon in 1457 (folios 120-127).