The first Jewish communities in Christian areas

After the arrival of the Muslims in 711, small Christian resistance groups were formed in the north of the peninsula, both in the Cantabrian area and in the Pyrenees. They would be the germ of the kingdoms that over the centuries would expand southwards into the territory of Al Andalus, in a complex historical process lasting eight centuries known as the Reconquista.

There is very little news about the Jewish communities in these Christian centres in their first centuries of existence. While Al Andalus was experiencing authentic cultural and economic splendour, in the north there were only a few small and scattered Jewish quarters. The most important in early times was that of Barcelona, of which there is news from the 9th century that speaks of several Jewish properties on the land surrounding the city. In the area of Aragon we can mention the Jewish quarters of Jaca and Ruesta, and in Navarre those of Pamplona and Estella. In León there was already an important Jewish quarter in the 10th century and in Castile the best known of this period was that of Castrojeriz. Jewish communities were especially scarce in Galicia, where we can mention the small community that lived in the vicinity of the monastery of Celanova.

From a legal point of view, Jews were considered royal property in all Christian kingdoms and were theoretically protected by kings and lords. In times of weak authority, they were exposed to attacks, in a general context of great insecurity and instability. In addition, discriminatory ordinances against them appeared regularly, although with little practical effect. Their status was that of "servi regis", a kind of servitude to the Crown. In fact, there are frequent documents in which kings speak of "my Jews".

As for the social and economic situation of Jews in these first centuries of the High Middle Ages, one can quote José Luis Lacave in "The Jews in Spain":

At this time the basis of subsistence of the Jews was the land; they themselves cultivated their fields, although a certain tendency towards urban trades and incipient commerce was already emerging. Documents occasionally tell us about Jewish tailors, shoemakers, silversmiths and goldsmiths, and also about Jews engaged in the silk or linen trade.

The Jews and the Reconquista

From the 11th century onwards, as a consequence of the disintegration of Al-Andalus, the Christian kingdoms began a more active policy of expansion towards the south with the aim of gaining more and more territory from the Muslims. In this context, large areas of the territory and urban centres were incorporated, which needed to be repopulated quickly and efficiently to ensure that they remained in Christian hands. This circumstance led to a significant improvement in the living conditions of the Jews, since on many occasions significant legal and economic benefits were offered to those who settled in the recently incorporated territories.

Relations with the Christian population changed and during this period organised communities emerged, influential in trade and industry, especially in the north-west quadrant of the Peninsula. The offer of privileges and freedom by several Leonese monarchs attracted numerous Jews who actively participated in the repopulation. Many of them came from the south, from the area controlled by the Muslims, which they decided to leave in the face of growing instability and attracted by the advantages offered in the Christian kingdoms. This population transfer produced a transformation in Spanish Judaism, with a growing influence of currents of thought arriving from the East, to the detriment of the Franco-German Jewish tradition.

Jewish communities became increasingly stable and prosperous, developing under royal protection, even in areas controlled by monastic communities or those belonging to the nobility. In fact, it was during this period that we find the first examples of Jews occupying important positions in the administration of the Christian area. Thus, for example, the military leader known as El Cid employed Jews as treasurers, financial agents, lawyers and administrators. Similarly, it is believed that King Alfonso VI surely employed the Jew Joseph ha-Nasi Ferrizuel, called Cidellus, as a doctor and financier, who did much to help his coreligionists. This inaugurated a tradition that would be constant in the Spanish Middle Ages, that of employing Jewish courtiers who, although they remained faithful to their religion, exercised considerable authority over the inhabitants of the kingdom.

The initiative to give positions of responsibility to members of the Jewish community increased as the Arab influence grew, since in Muslim states it was common for Jews to occupy the highest positions in the State. In general, they combined these tasks with their dedication to science and literature, so that efficiency in administration was added to the cultural splendor that the Christian courts wanted to imitate.

Furthermore, in the Christian kingdoms the figure of the financier practically did not exist, due to the traditional condemnation of usury by the Christian religion. The Jews who arrived from Al-Andalus thus had a clear business opportunity before them, and soon became lenders not only to kings but also to bishops and nobles. In this way they secured their socio-economic position and in some way became indispensable to the authorities who ran the State.

Thus, between the 11th and 13th centuries there was a situation of general well-being for the Jews in the Christian kingdoms, which contrasted clearly with the enormous difficulties they faced in other European territories. This logically caused an immigration of Jews to the Peninsula, with new populations settling mainly in urban centres under the protection of the king, although also in places dependent on local lords or ecclesiastical authorities. This was possible because in certain circumstances the king granted some nobles or members of the church the right to "have Jews", although in general this was an exclusive privilege of the monarch.

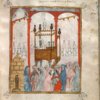

The aljamas were the most common form of organization of the Jewish community in Christian cities. It had legal status and enjoyed administrative and judicial autonomy. There was a state official who was in charge of it and was responsible for collecting the special taxes that the aljama had to pay to the royal treasury.

There were frequent individuals who rose in their social and economic position within the framework of the reconquest. Administrative skills and knowledge of languages made it easier for them to take charge of collecting taxes, a task that they often complemented with the practice of medicine and astronomy. The monarchs increasingly trusted them, not only in matters relating to the Treasury, but also in relation to diplomatic activity and other matters of State. These prominent figures in the political, cultural and economic life of the Christian kingdoms did not appear until the time of the expulsion, especially in the kingdom of Castile.

In many cases, their social status was similar to that of the nobility and they were also usually landowners, since it was common for them to be given large tracts of land as payment for their services or to meet the repayment of loans. Their lifestyles were not too closely limited to Hebrew law and they were often enveloped in luxury and ostentation, forming a kind of Jewish aristocracy that raised certain suspicions inside and outside the aljamas. However, it was common for them to use their advantageous position in the court to promote laws that benefited the members of their religion, so in general their existence was viewed with pleasure and respect by the rest of the Jews.

Among them we can mention Yosef ibn Ferruzel (Cidiello), Yehuda ibn Ezra, Semuel ibn Sosán, Isaac de la Maleha, Abraham de Barchilón, Juçaf de Écija, Samuel ha Leví, Meir Alguadex, Abraham Beneviste, Abraham Seneor and Isaac Abravanel in Castile; and Eleazar, Yehudá de la Caballería, Mosé Alconstantini, Yosef Ravaya and Hasday Crescas in Aragón; in Navarre the most notable was Yosef Orabuena. (José Luis Lacave, "Jews and Jewish quarters")