The cultural splendour of the Caliphate of Córdoba

The Visigoth kingdom was immersed in one of its constant internal conflicts when the Muslim conquest of the Peninsula began in 711. It is proven that the Jews welcomed the new lords and collaborated with them in the conquest process. There was even a Jewish contingent that fought alongside the Muslims under the command of Kaula al-Yahudí in the battle of Guadalete, in which King Rodrigo and some of the kingdom's main nobles died. Furthermore, as the conquest continued to the north, the Muslims entrusted the government of different cities to members of their Jewish communities. This occurred, for example, in Córdoba, Málaga, Granada, Seville and Toledo.

With the new Islamic political reality, Jews, like Christians, came to be considered “dhimmis” or “People of the Book”, since, being monotheistic religions and sharing part of the theoretical basis of Islam, it was understood that they had received part of the “revelation”. In this way, they enjoyed a certain status of protection that allowed them to preserve their original faith. However, they were subject to the payment of a tax exclusive to non-Muslims, known as “jizia” or “jizya”.

In any case, the new political reality brought with it a renaissance of the Jewish communities that were settled on Hispanic soil, since the persecutions they suffered during the Visigothic period were considered to have ended. Those who had been forcibly converted were able to return to their primitive faith and many Hebrews from other places, encouraged by the new situation that was experienced in the peninsula, decided to settle there. (Montes Romero-Camacho, Isabel, "Andalusian Jews in the Middle Ages", in "Andalusia in History", no. 33)

After a few initial decades in which the territories dominated by Islam in the Peninsula formed an emirate dependent on Damascus, in 756 Abderramán I came to the throne, inaugurating the Independent Umayyad Emirate with its capital in Córdoba. This was the beginning of a period of prosperity for the Jews, who would increasingly collaborate with the authorities, occupying positions of responsibility and controlling lucrative economic activities.

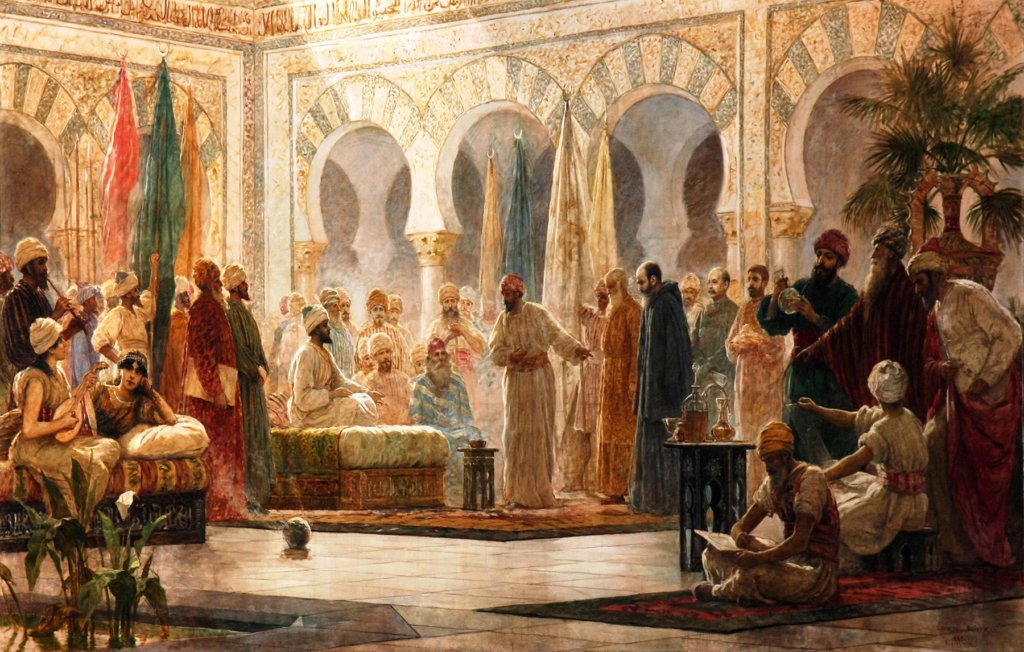

This progress would reach its climax with Abderramán III, who would proclaim himself caliph in 929. Under his reign and that of his son, Alhakén II, there would be a true golden age of Andalusian Judaism. During this period, figures such as Hassday ibn Shaprut, a court physician and diplomat, and poets and writers such as Dunash ben Labrat and Menahem ben Saruk, came together in Córdoba. Particularly relevant was the figure of Rabbi Moses ben Hanoch, who founded a Talmudic school that contributed especially to Al-Andalus in the 10th century experiencing one of the moments of splendour in the history of Jewish culture.

"The civilization of the Caliphate of Córdoba in the times of Abderramán III". Dinisio Baixeras, 1885. Wikimedia Commons.

Taifa Kingdoms

The period of cultural splendour experienced in the first centuries of Al-Andalus was short-lived and the political structure of the Caliphate would end up collapsing after the death of the leader Almanzor in 1031. Thus began the period known as the Taifa Kingdoms, in which the territory was divided into numerous emirates governed by dynasties such as the Abadíes in Seville, the Hammudies in Malaga, the Ziríes in Granada or the Beni-hud in Zaragoza. The instability and violence that took hold of Córdoba in the last years of the Caliphate caused many Jews to abandon it, heading mainly to Malaga, Granada, Toledo, Murcia and Zaragoza.

Once the new kingdoms were established, Jewish communities began to flourish again in many of them, often promoting economic progress and the cultural dynamism of their capitals. Once again, prominent Hebrew personalities appear occupying important positions in the administration of the different kingdoms.

A good example is the Taifa of Zaragoza. During the reign of Mundir II, the poet and Talmudist Yekutiel ben Isaac was appointed grand vizier of the kingdom, which was equivalent to a head of government or prime minister, which shows the confidence of the Muslim authorities in the members of the Jewish community. The disorders that followed a coup d'état in 1039 would end his life, but a few decades later, another Jew, also a poet, would again occupy the post of vizier. This was Abu al-Fadl ibn Hasdai, who took office in 1070 during the reign of Al-Muqtadir. He decisively promoted science, arts and culture in the kingdom, being largely responsible for its political and intellectual rise.

In Seville, too, the Jews enjoyed a prosperous situation during the 11th century, mainly during the reign of Al Mudamid, the last king of the Abadi dynasty. His court was a cultural splendour, in which prominent members of the Jewish community actively participated. One of them was the scholar Isaac ibn Albalia, who was appointed personal astronomer to the king. Also notable was the role of Joseph ibn Migas, who was employed as one of the most prominent diplomats in the kingdom.

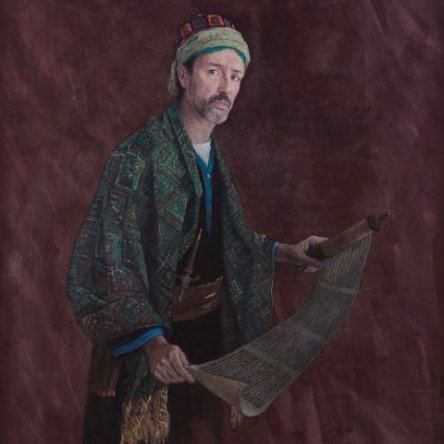

But the Taifa in which the Jews achieved their greatest social, economic and political relevance was undoubtedly that of Granada. The Talmudist and linguist Samuel ha-Levi ibn Nagdela (Nagrela) arrived in this city fleeing from Cordoba, and soon won the favour of the vizier of King Habus of Granada. The latter appointed him private secretary and recommended him to the king as an advisor. Upon the death of the vizier, the king appointed him minister and entrusted him with the administration of diplomatic affairs. Samuel also worked as a rabbi and took an active interest in science and poetry. He retained his position at court under King Habus's son Badis, whom he assisted against his elder brother Balkin. Samuel remained the protector of his coreligionists, who in Granada enjoyed full civic equality, being eligible for public office and for service in the army.

Upon Samuel's death in 1055, he was succeeded as minister by his son, Joseph ibn Nagdela. His pride and ambition aroused the enmity of some Muslims, who saw pre-eminent positions in the administration being occupied by infidels. In 1066 a conspiracy was organised which ended with Joseph's assassination. Inspired by the fanatics, the Muslims then attacked the Jewish quarter of Granada, provoking the first persecution and massacre of Jews in Muslim Spain. Many survivors fled to other cities, especially Lucena, further developing the importance of the Jewish community in that city.

Samuel ha Nagid - Ibn Nagrella, in an imaginary portrait by Daniel Quintero (2017). Museo Sefardí de Toledo.

Almoravids and Almohads. The expulsion of the Jews from Al Andalus

The Castilian advance against the kingdom of Seville under Alfonso VI prompted King Al-Mu'tamid to ask for help from the Almoravids, a fanatical and warlike religious sect from across the Strait of Gibraltar. They defeated the Christian troops at Sagrajas (1086), a battle in which many Jews are known to have fought, both on the Muslim and Christian sides. The Almoravids thus took control of Muslim Spain. Their leader, Yusuf ibn Tashfin, did nothing to improve the welfare of the Jews. On the contrary, he strove to force the large and wealthy community of Lucena to embrace Islam. Under the reign of his son Ali (1106-1143) the position of the Jews was more favourable. Some were appointed "mushawirah" (collectors and custodians of royal taxes). Others entered the service of the State, holding the title of "vizier" or "nasi". The ancient communities of Seville, Granada and Cordoba prospered again.

But the power of the Almoravids was short-lived. A North African fanatic, Abdallah ibn Tumart, emerged around 1112 as the defender of Muhammad's original teachings on the oneness of God, and became the founder of a new party called the Almohads or Muzmotas. Upon Abdullah's death, Abd al-Mumin took command and continued his fight against the Almoravids, first in North Africa and from 1147 in the Peninsula, achieving control of all Muslim Spain in less than a year. The new conquerors brought a much more rigid and uncompromising religious vision, forcing Jews to accept the Islamic faith or leave the territory. They confiscated their property and took their wives and children, many of whom were sold into slavery. The most famous Jewish educational institutions were closed and the beautiful synagogues destroyed everywhere.

One of the Jews who were forced to leave the country in the context of the expulsion decreed by the Almohads was the famous Maimonides, one of the most outstanding personalities in the history of Judaism. He was a doctor, philosopher, astronomer and rabbi, born in Córdoba in 1135. His contributions in various fields made him an intellectual reference for both Jews and Muslims during his lifetime, with his work Mishneh Torah standing out in religious matters, which is still considered one of the pinnacles of the codification of Jewish laws and ethics. After the Almohad conquest of Córdoba, Maimonides and his family had to flee, wandering through various peninsular territories to finally end up in Fez, in present-day Morocco. He spent only five years there because the Maghreb was also under Almohad rule, so that he ended up settling in Egypt, where the center of the Fatimid Caliphate was then located. There he was able to continue his career until his death in Cairo in 1204.

The terrible persecutions of the Almohads lasted ten years. Due to these persecutions, many Jews tried to embrace Islam, but a large number fled to Castile, where Alfonso VII received them with hospitality, especially in Toledo. Others fled further north to Spain and even to Provence, where the Ḳimḥis family took refuge, for example. Several attempts by the Jews to defend themselves against the Almohads were unsuccessful, as happened with the brave Abu Ruiz ibn Dahri in Granada in 1162.

The Almohads were finally defeated by a coalition of Christian kingdoms in the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212), after which Al Andalus lost its political unity again and the Taifa kingdoms reappeared.