The Hospital de la Caridad is the headquarters of the brotherhood of Santa Caridad, whose purpose is to assist sick people with few resources. It was founded in the 15th century and still carries out valuable healthcare work in Seville today. The architectural complex that has survived to us is mostly dated to the 17th century.

HISTORY

In its origins, the brotherhood was mainly dedicated to paying for the burial of those executed and drowned in the river, functions that expanded over time, increasingly focused on assisting the sick without resources. In the 16th century it is known that they had their headquarters in a small chapel dedicated to Saint George, which was in the same location as the current temple.

It is a space that was part of the old Royal Shipyards of Seville, an immense area of seventeen ships dedicated since the 13th century to the construction, repair and storage of ships.

In the middle of the 17th century, it was decided to replace the original chapel with a new church and the adjacent construction of a large hospital to care for the sick. For this, the space of three of the ships of the old shipyards was given to them.

The works began in 1645 under the direction of Pedro Sánchez Falconete and received a notable boost when Miguel de Mañara entered the brotherhood, who would be elected elder brother in 1663.

Mañara was a wealthy Sevillian merchant who found meaning in his life in Santa Caridad after the death of his wife. Various testimonies from the time, including some references from himself, speak of him leading a very disorderly life in his youth, which is why since the 19th century he has been linked to the figure of Don Juan Tenorio, the most universal literary archetype. from among those who emerged in Seville. Tradition has wanted to see in Miguel de Mañara the character on which Tenorio is based, although currently we know that neither the facts of his biography nor his chronology allow us to support this statement.

What is certain is that his arrival to the leadership of the brotherhood was a great boost for it, managing to attract large sums of money donated by the best-placed families in the city, among which Mañara was used to moving.

The Hospital complex consists of two enormous elongated rooms for caring for the sick, more than 40 meters long, which run perpendicular to Temprado Street. Before them, a rectangular porticoed patio opens, divided in two by a gallery in the center. To the left, and also perpendicular to the street, is the church, with a single nave. It has its main façade at the foot and a side access from the patio.

HOSPITAL

On the outside, the only part that has decoration is the one that corresponds to the church. The rest of the façade is very austere, with hardly any decoration, with the exception of the two pilasters that flank the main door and that support the projection of a small balcony.

After a small hall, you access the first of the two patios, separated only by the passage supported by a gallery of columns that we have mentioned. In all probability they were designed by the great architect of the Sevillian baroque, Leonardo de Figueroa, who is known to have been master builder of La Caridad since 1679.

Both have porticoes on three sides, with the exception of the one that faces the large naves of the hospital. They do so through semicircular arches supported by Tuscan marble columns on the first floor. The second floor is closed, although large protected windows with a small balcony open to the patio, coinciding in location with the arches on the ground floor.

In the center of each patio we find two monumental fountains with allegorical representations of Faith and Charity. They were made in Genoa and it is documented that he commissioned them for this hospital in 1682.

On the walls of the patio you can admire a set of seven tile panels in shades of blue on white that represent various scenes from the Old and New Testament. They were made in Holland, probably in Delft, at the end of the 17th century and arrived at the hospital as a donation from the Descalzos convent of Cádiz.

CHURCH OF SAINT GEORGE

Facade

The hospital temple maintained the dedication of Saint George, to whom the primitive chapel around which the brotherhood was founded was dedicated. Its façade stands out from the rest of the hospital for its height and decorative richness, despite its relative simplicity, especially in comparison with the decorative exuberance that we will see inside.

It is arranged following the logic of an altarpiece, articulated on two levels and the architectural elements, such as pilasters and pediments, constitute the main decorative element. Despite its classic lines, it is a façade of great originality, achieved through the combination of white and ocher surfaces, between which five ceramic panels in blue and white tones are arranged.

In the first body, the access door is framed by two pairs of attached columns that support an entablature with a split curved pediment. Between each pair of columns are the baked clay figures of San Fernando and San Hermenegildo, the two saints traditionally considered "patrons" of the Spanish Crown.

On the second level, a balcony framed by Corinthian pilasters opens in the center of the split pediment of the first floor. Above it, a niche houses the central ceramic panel, with an allegorical representation of Charity.

On each side are two other ceramic panels, the lower ones finished with a curved pediment and the upper ones with a straight pediment. On the first level, "Saint Michael against the dragon" and "James defeating the Saracens" are represented. Saint George is the patron saint of the hospital in memory of the chapel around which it was founded and Santiago is the patron saint of Spain. They are arranged here symbolizing saints who "fight against the forces of evil to impose the Christian faith." Above them, the ceramic panels of Faith and Hope, which with that of Charity that we mentioned before complete the three theological virtues. Traditionally, the design of the five ceramic panels has been attributed to Murillo, although due to its formal characteristics it does not seem that this statement has a historical basis.

The façade is topped by a central attic with a straight pediment and two lateral brick pinnacles. These forms are quite common in the Sevillian baroque and their similarity to works by Leonardo de Figueroa has led to at least the completion of the façade being attributed to him.

Attached to the head of the left side of the church is a small bell tower, not very visible given its location. It was built in 1721 under the direction of Leonardo de Figueroa. In it, the architectural elements described on the temple's façade are repeated, on a smaller scale. The original spire is striking, abundant in sculptural and ceramic decoration despite its small dimensions.

Inside

The church has a very simple, rectangular plan, with a single nave and a flat head. It is covered by a barrel vault, except in the central space before the presbytery, which is covered with a hemispherical vault on pendentives, as wide as the nave itself. At the foot there is a high choir, supported by three arches on Tuscan marble columns, the lateral ones semicircular and the central one lowered and wider.

The main entrance is located at the foot and upon entering the church we realize that we are facing one of the most exceptional complexes in the history of art in the city. It is not only a collection of singular works of great merit, but together they form a homogeneous and perfectly coherent discourse with the Baroque world in which it was created.

Iconographic program: works of mercy as a path to salvation

The iconographic program was designed by Miguel de Mañara, with the aim of transmitting the idea of the transience of life and the irrelevance of achievements and material possessions when the last moment comes. It tells us that we are all headed to the same end and only the practice of Christian virtues, among them charity, guarantees the salvation of the soul. The aim was to stir the conscience of anyone who entered the church and promote donations through fear of eternal damnation.

The speech begins with the two canvases that are on both sides as soon as you enter the temple, on two access doors to side rooms. These are two works by Juan Valdés Leal from 1672 that have death as their central theme. They are of such quality that it is not unreasonable to define them as the best works with this theme in the entire history of universal art.

The first is titled "In ictu oculi", which could be translated as "in the blink of an eye". It shows a skeleton holding a scythe in one hand while with the other he extinguishes the flame of a candle, symbolizing that it takes only an instant to go from life to death. Next to him, a series of symbols of earthly glory are piled up: luxurious clothing, a royal crown, a papal tiara, colorful books, scepters, armor... None of all that matters when the final moment comes, death is carried away without respects both for a supreme pontiff and for a humble peasant.

The second painting, located directly opposite, is titled "Finis Gloriae Mundi" ("The End of the Glory of the World"), as can be read on a cloth banner that appears in the foreground. It is set inside a tomb and we see the decomposed corpses of a bishop and a knight of the Order of Calatrava. Despite the deterioration, both show off their richest clothing. From the top, the arm of Christ emerges, recognizable by the stigma in the palm of the hand, holding a scale with two plates. One of them reads "NI MÁS" (no more) and the symbols of the capital sins rest on it. The other reads "NI MENOS" (no less) and holds the symbols of Christian virtues. The message is clear, when the final moment comes, titles, honors or material possessions are of no use, only good and bad actions will be taken into account. He is thus encouraged to do everything possible so that, when that moment comes, the plate of virtues outweighs that of sins.

El siguiente hito de esta narración consiste en mostrar el camino a la salvación a través de las obras de misericordia, que nos permiten ejercer la caridad ayudando al prójimo. La doctrina católica define siete obras de misericordia “corporales” y se encargó a Murillo la realización de seis lienzos para representar las seis primeras. Esto es debido a que la séptima, “enterrar a los difuntos”, quedaría representada por el retablo mayor del que hablaremos más tarde.

Hoy las podemos contemplar a ambos lados, en la parte superior de los muros de la nave y del ante-presbiterio. Sin embargo, las cuatro obras originales que se encontraban más cercanas a la entrada fueron sustraídas en 1810 durante la ocupación napoleónica de la ciudad y en la actualidad se hallan repartidas por diversos museos del mundo. De hecho, la talla de los museos en los que se encuentran es un buen indicativo de la calidad artística del conjunto original. Hoy se encuentran dispersas entre la National Gallery de Londres, el Museo de Ottawa, la National Gallery de Washington y el Museo del Ermitage en San Petersburgo.

Desde 2007 se pueden contemplar en la iglesia una serie de copias fidedignas realizadas a mano. En el muro de la derecha se sitúan "La curación del paralítico", que alude a la práctica de atender a los enfermos, y "San Pedro liberado por el ángel", que hace referencia a la obligación de redimir al cautivo. Justo enfrente, en el muro de la izquierda, encontramos "El regreso del hijo pródigo", en referencia al mandato de vestir al desnudo, y "Abraham y los tres ángeles", que alude a la obligación de dar posada al peregrino.

El ciclo dedicado a las obras de misericordia continúa con los dos grandes lienzos situados en la parte superior de los muros del ante-presbiterio. Afortunadamente, en este caso sí que estamos ante los originales de Murillo. A la izquierda vemos a "Moisés haciendo brotar el agua de la Roca", que hace alusión a la obligación de dar de beber al sediento. Justo enfrente, se representa "La multiplicación de los panes y los peces", en referencia al mandato de dar de comer al hambriento.

Main altarpiece

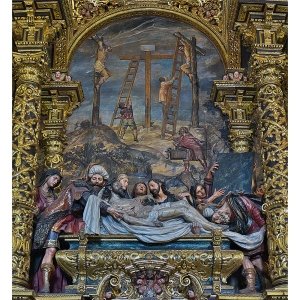

As we said, the seventh work of mercy, "burying the dead", is represented in the church by the central scene of the main altarpiece. It is a set made by Bernardo Simón de Pineda between 1670 and 1674, making up one of the most outstanding altarpieces of all of the Spanish Baroque.

It is divided into three streets delimited by four beautiful Solomonic columns. The entire center is occupied by the scene of the "Holy Burial of Christ", made by Pedro Roldán, who here executes one of the most accomplished works of his long career. He manages to transmit through the gestures and postures of the characters a great compositional harmony that does not detract from the drama of the scene represented. In the background, and in low relief, there is a dark Mount Calvary, which in a very effective way conveys the sensation of depth and compositional unity of the entire complex.

In the side streets there are San Jorge and San Roque and in the attic the allegories of the three theological virtues appear, from left to right: faith, charity and hope. The entire altarpiece is dotted with a large number of cherubs, child and youth angels, sometimes acting as caryatids, which help to emphasize the sensations of dynamism and decorative exuberance. Crowning the entire complex, a group of four angels hold a cartouche with the name of God in Hebrew.

Other altarpieces and canvases

As we said, the church of the Hospital de la Caridad is distinguished by the high quality of its altarpieces and paintings. The four side altarpieces of the church, like the main altarpiece, are the work of Bernardo Simón de Pineda, a sculptor from Antequera who is among the best sculptors of altarpieces of the 17th century in Seville. The most outstanding canvases are, like those already mentioned about the works of mercy, the work of the brilliant Murillo, who created one of his most outstanding pictorial sets for this church.

On the left wall, starting from the entrance, there is the canvas of "Saint John of God carrying a sick man", a work by Murillo from around 1662. It is a beautiful canvas that shows an angel helping the saint in his work. assistance to the sick, in a topic closely linked to the function of the hospital.

Next is an altarpiece that frames the canvas of "The Annunciation", also a masterful work by Murillo dated around 1670.

Between the nave and the ante-presbytery there is an iron and wood pulpit that stands out for its beautiful design. Culminating it, an allegory of Pedro Roldán's Charity appears and a curious monstrous animal is represented holding the ladder. It is a representation of the conquered evil sculpted by Bernardo Simón de Pineda.

Next, in the ante-presbytery, there is the altarpiece of the Virgin of Charity, presided over by an anonymous image of the Virgin and Child dated to the beginning of the 16th century, in which certain features of the late Gothic period are still noticeable. . In the attic, there is a small canvas by Murillo with the "Salvador Niño", from around 1671, which has been described as one of the most beautiful children's prototypes of his production.

On the right wall, starting again from the foot of the church, we find a beautiful composition by Murillo that represents "Saint Elizabeth of Hungary caring for the stinging." It is dated 1672 and refers to the second obligation of the brotherhood, after that of burying the dead, which was to care for the sick.

Next we find the small relief of Ecce Homo, made in baked clay by the García brothers from Granada at the beginning of the 17th century.

The next altarpiece is that of the Christ of Charity, presided over by a work by Pedro Roldán that shows Christ kneeling, looking towards heaven, praying in the moments before the Crucifixion. It stands out for its moving face, one of the most accomplished in the sculptor's career.

Already in the ante-presbytery, there is the altarpiece of San José, with an image of the saint carved by Cristóbal Ramos in 1782. The chronological difference with the altarpiece, which is a century earlier, and the small size of the sculpture with respect to the niche, show that it is not the work originally intended for this place. Historically, this altarpiece was occupied by a beautiful carving of Saint Joseph from the 17th century from the circle of Pedro Roldán, which is currently located in one of the Hospital's rooms, the so-called Sala de San José.

In the attic you can admire another of the jewels that Murillo left in this church, a small canvas of "San Juan Bautista Niño", of extraordinary and tender beauty.

Tempera paintings on the dome and walls

Between 1678 and 1682, Juan Valdés Leal was in charge of the pictorial decoration of the upper part of the walls and the dome of the antepresbytery.

Under the arches that support the dome, flanking the windows, are represented four "alms" saints, whose holiness derives from their assistance to the poor: Saint Martin, Saint Thomas of Villanueva, Saint Julian and Saint John Almoner. The four Evangelists are represented on the pendentives and on the dome's gallons there are eight beautiful angels carrying symbols of the Passion of Christ.

If we look up when leaving the church we can admire one last masterpiece of this church. This is the tempera painting "The Exaltation of the Cross" that Valdés Leal made in 1685 on the semicircular wall under the vault, just above the high choir. His message comes to complete the iconographic discourse that we have been observing in the church. The central idea is the statement derived from the Gospel that no rich man will enter through the gate of the kingdom of heaven. The explanation of the episode represented is quite complex. It is based on a passage from the Golden Legend that Enrique Valdivieso describes like this in the "Guide to Holy Charity":

...tells the moment in which the emperor of Byzantium, Heraclius, after having rescued the Cross of Christ that the Persian monarch Khosrau had stolen from Jerusalem, appears before the gates of this city with the intention of entering triumphantly into she. At that moment several prodigies occurred, first noticing that thick blocks of stone began to fall from the wall and the gates of the city, interrupting the passage of the procession. Also at that moment an angel appeared to the emperor Heraclius and his entourage, telling him that through that door Christ had entered Jerusalem riding on a donkey and accompanied by his humble procession of Apostles, and that he could not make ostentation by entering with his imperial court. dressed in luxurious finery.

The angel's clear and direct message was immediately understood by the emperor Heraclius and therefore he proceeded to take off his clothing, a gesture that his entire procession imitated, as he prepared to enter the city with modesty in his attire and inner recollection; In this way they managed to enter Jerusalem and return the Cross of Christ. The plot of this story, reflected in the painting, points out that in the same way that Heraclius cannot enter the city clothed in his pomp and pageantry, no one will enter Paradise with his riches.