Currently, the Hospital is the headquarters of the Focus Foundation and the Velázquez Center is located in its rooms, dedicated to the dissemination of the Sevillian painter, exhibiting some works of his authorship along with some magnificent pieces by contemporary authors, such as Murillo, Valdés Leal , Juan Martínez Montañés and Pedro Roldán, among others.

Cloister

The building is articulated around a main patio surrounded by a porticoed gallery with marble columns that support semicircular arches on the first floor. The upper galleries are closed and open onto the patio through large windows with wrought iron balconies, framed between reddish brick pilasters.

In the center of the patio, its original fountain stands out, which is located at a lower level with respect to the rest of the patio. It is accessed through decreasing concentric steps. The explanation of its location is due to the difficulty in the existing water supply in Seville in the past. This location allowed water to enter directly and safely inside. The tiles in the fountain are original from the period, forming a multitude of geometric shapes in blue and yellow tones, very characteristic of Andalusian heritage ceramic art.

Church

The design of the church was drawn up by Leonardo de Figueroa, the great architect of the Sevillian Baroque, to whom such notable works in the city are due as the Church of La Magdalena, El Salvador or San Luis de los Franceses.

In the case of Los Venerables, the temple responds to the traditional form of Sevillian churches from the second half of the 17th century, with a single nave covered by a barrel vault with lunettes and transverse arches. In the presbytery there is a transept, slightly marked on the floor plan of the building, covered in the center by a semicircular vault, ribbed and without drum. This dome is not visible from the outside, as it is covered by a hipped roof.

Although the structure of the church is quite simple, its profuse pictorial decoration based on frescoes, as well as the richness of the works of art that it treasures, make it one of the most important ensembles of the Sevillian Baroque.

The paintings in the church respond to the design of the great Sevillian painter Valdés Leal, although his advanced age meant that a large part of them were executed by his son, Lucas Valdés. In general, those located in the presbytery, in the area closest to the main altar, are considered to respond to the direct execution of Valdés Leal, while those in the rest of the church would have been undertaken by his son Lucas Valdés, although following the design created by his father.

The technique used for the execution of all of them is that of tempera painting, which had already been used by Valdés Leal at the Hospital de la Caridad, with touches in oil.

The iconographic program focuses on the exaltation of the priesthood, in relation to the purpose for which the Hospital de los Venerables was built, as a residence for elderly priests. We also find numerous references to San Pedro and San Fernando, as titular saints of the temple. We see that a very characteristic pictorial effect of Baroque art is used profusely: trompe l'oeil. It is about recreating scenes in illusory spaces extended beyond the architectural space that contains them. Thus, a reality full of light and movement is created, through garlands, fruit sets, vases, jaspers and ovals. Through painting, other materials are simulated, such as tapestries, metal medallions or stone sculptures.

A monograph would be necessary to describe the set of paintings in the church of Los Venerables. As an example, we can cite those located in the vault of the presbytery, above the main altar. There Valdés Leal located a 'Christ the Savior, triumphant of his Passion and Death', represented with great success in the treatment of perspective. He is framed by a triangle, symbol of the Trinity and crowned by the name of Christ in Hebrew. The lower vertex of the triangle falls on the center of a circle, which symbolizes eternity. Located at the feet of Christ, open, the Book of the seven seals, in an image that resembles that of the apocalyptic Lamb. At the sides of Christ, two elderly priests dressed in pontifical adore and incense his body. From the elements of martyrdom located at the feet of these characters, an inverted cross and an anchor, it can be deduced that they are Saint Peter and Saint Clement Pope, which is confirmed by the papal iconographic symbols located in the corners. The allegories of Charity and Humility close this set. These are two virtues that must adorn the priesthood.

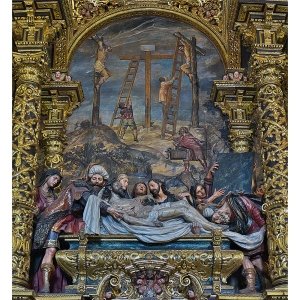

The current main altarpiece has nothing to do with the first one that was built in the church; although if it conserves some works that conformed it. The altarpiece that we see today was completed in 1889, being the work of Vicente Ruiz. This is not a particularly fortunate altarpiece in its composition, taking advantage of abundant material from carrying in its structure, especially from the previous altarpiece.

In the main body is the large canvas of the 'Last Supper', which, like the tabernacle, belonged to the old altarpiece. This work, previously considered to be from the first third of the 17th century, belongs to the production of Lucas Valdés. It has a style that is quite different from traditional Sevillian painting, with a rather archaic composition and a gloomy atmosphere.

The upper body of the altarpiece contains three niches with pictorial representations. In the central one there is a canvas with 'The Apotheosis of San Fernando', a work also by Lucas Valdés, although in this case of great quality. Fernando III appears on a pedestal next to the weapons and clothing of the defeated Muslims. San Fernando is flanked by two young matrons who can be identified with Seville liberated and La Paz. On the sides, in the smaller niches, there are two canvases of San Clemente and San Isidoro, made by the Sevillian painter Virgilio Mattoni in 1891.

On the walls of the church, among its rich tempera decoration, there are a series of altarpieces made between the 17th and 19th centuries, which stand out more than for their intrinsic quality because they house a series of interesting sculptural and pictorial works.

To mention just a few, we can talk about two of the altarpieces on the right side. One dedicated to the Immaculate Conception, presided over by a canvas by José María Ruiz y García, from the beginning of the 17th century, or the one dedicated to Saint Joseph, with a beautiful sculpture from the end of the same century and by an anonymous author.

On both sides of the main door, at the foot of the temple, there are two magnificent seated works that represent San Clemente and San Fernando. They are works by Pedro Roldán from 1698 and both were polychromed by Lucas Valdés.

Sacristy

From the right side of the transept there is access to a small sacristy that houses one of the jewels of this Hospital. It is about the paintings of the vault, one of the masterpieces of Valdés Leal. The painter creates an imaginary architecture here, in which angels descend under the balustrade carrying the Holy Cross. Despite the small dimensions of the space, the author manages to convey the sensation of three-dimensionality, to which is added the enormous skill in representing the different textures.

Velazquez Center

The Velázquez Center, promoted by the Focus Foundation, exhibits in some of the rooms of the Hospital practically the only works of the great Sevillian painter that can be seen in his hometown.

Among them, we find an Immaculate Conception that constitutes one of the first known works of Velázquez, who already showed here his enormous capacities despite his young age. The Virgin appears represented following the patterns dictated by her father-in-law Francisco Pacheco and stands out for the great naturalism of the image. Next to it, by the same author are an 'Imposition of the chasuble on San Ildefonso' and a beautiful and masterful 'Santa Rufina', which is perhaps the most emblematic work of the Hospital de los Venerables.

In addition to Velázquez's works, there is a selection of high-quality paintings by contemporary artists. Authors such as Francisco Pacheco, Zurbarán or Murillo are represented, of whom we can admire a magnificent 'Penitent Saint Peter', originally painted for the church of this hospital. The work was stolen by the French during the Napoleonic invasion and returned to Seville in 2014 thanks to its acquisition by the Focus Foundation.

In the same room there is also a View of Seville by an anonymous author and dated around 1660. It is one of the most beautiful historical panoramic views of the city among those that have survived to this day.

Added to the pictorial works are two sculptures by Martínez Montañés, one of the great masters of the Sevillian Baroque, of which an Immaculate Conception and a youthful Saint John the Baptist are on display. Both come to complete the extraordinary artistic collection of the 17th century exhibited in the Hospital.

Upper gallery of the Cloister

In the upper gallery of the cloister, a series of pictorial works are exhibited, mainly also from the 17th century, focused on biblical and landscape themes. Due to their historical value, those located leaving the stairs to the right can be highlighted. They are two works by Lucas Valdés, related to the history of the Hospital de los Venerables. Scenes of assistance to poor priests are represented by valuable gentlemen, who humbly provide this assistance service. Contrast, as can be seen, the presence of high lineage dresses with the threadbare smocks of the elderly priests who seek lodging and care within the walls of the hospital.

Old Nursing

An interesting collection of contemporary painting from the 20th and 21st centuries has been located in the rooms of the primitive infirmary of the hospital.

In it, the works of the Sevillian artist Carmen Laffón stand out in the first place, with her sketches for the official poster of Holy Week, illustrating a detail of the passage of the popular Virgin of Candelaria. In addition, we can see her work Woman seated from behind.

Among other authors, we can also highlight the watercolors of the Murcian painter Ramón Gaya.

In general, it can be a collection that allows us to appreciate the new conception of art in our days, far removed from the baroque themes that are exhibited in the rest of the Hospital's dependencies.