In the San Diego roundabout, at the northern end of the María Luisa Park, a structure in the shape of a triumphal arch is preserved with three openings that house the allegorical figures of Spain, in the center, and the city of Seville in its center. material and spiritual dimension, on both sides. The sculptures were made by Enrique Pérez Comendador and Manuel Delgado Brackenbury. In the central part of the plinth there is a fountain, whose spout, under the pedestal of the central sculpture, is a bearded character who spouts water from his mouth.

It was the central axis of the main entrance to the 1929 Ibero-American Exhibition site and was designed by the architect Vicente Través. The entrance actually had four doors, which faced the avenues of Portugal and Isabel la Católica on the left, and the avenue of María Luisa and the Seville Pavilion on the right.

This triumphal arch was conceived as the center of the monumental entrance to the exhibition site. In this way, the aforementioned allegories of Spain and Seville were placed, somehow symbolizing the welcome offered by the city and the nation as a whole.

Enrique Pérez Comendador, a young sculptor from Cáceres who was barely 28 years old at the time, was chosen to create the side sculptures. The work of this sculptor was quite prolific throughout his life, specializing above all in public monuments, since his style fit very well with the purpose of extolling the characters represented, by combining a realism of very classic forms with the simplification of the volumes and a renunciation of detail, which were considered to be typical of the “modern” style. He was always quite faithful to the academic opinions of the time in the execution of his works and showed a special ability to develop allegorical themes and the aggrandizement of heroic characters, so popular in official art during the Franco regime.

The artist called the two sculptures “The spiritual and material wealth of Seville”, although they were renamed in an article written by the poet Alejandro Collantes de Terán as “The sky and the earth of Seville” (el cielo y la tierra de Sevilla). These are two female figures with clear classical reminiscences, dressed in tunics that very clearly show the effect of wet cloths, so the round shapes of the bodies are perfectly visible.

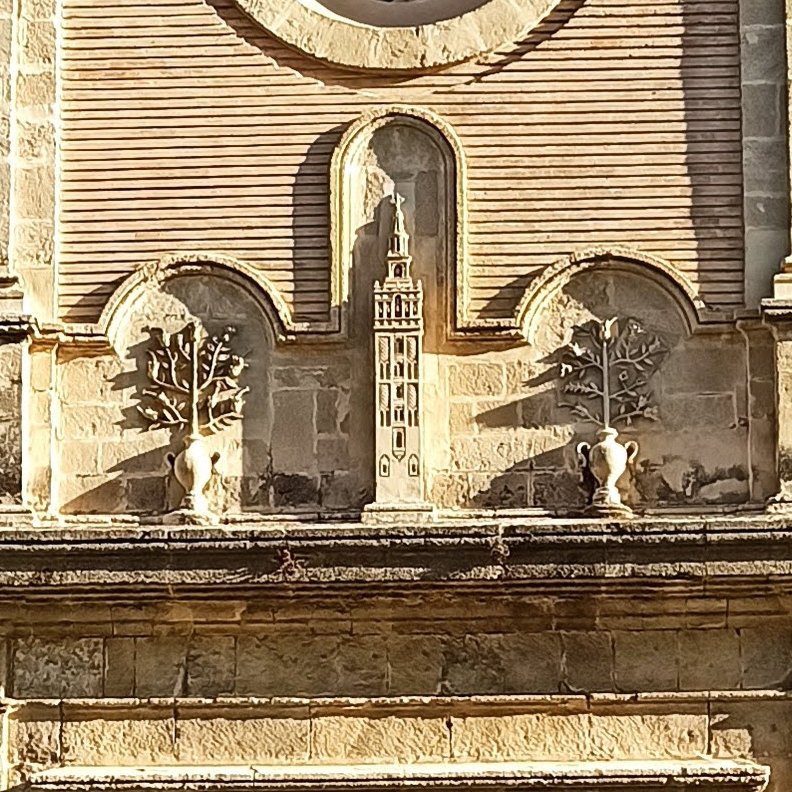

The figure located to the viewer's left is the material wealth of Seville. His shapes are more rounded and he has more ease in his posture. He holds an orange raised in his right hand and in his left he holds a bunch of grapes and a bunch of ears of wheat, as symbols of the fertility of the earth. His face has an expression between mischievous and friendly, framed by semi-tied hair with a certain Andalusian air, as shown by the loose locks that form snails around his face.

The other figure is the one that represents the spiritual wealth of Seville. Her main attribute is a small Inmaculada with mountain features that she holds in her right hand. With it, reference is made to the fierce defense that the city always made of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception and in general to its profound Marian character. In this case, the allegorical figure shows a somewhat forced posture, with more rigid features and less naturalism, probably seeking greater solemnity. Her face is reminiscent of sculptures from the archaic period of Greek art, due to the lack of expressiveness and that characteristic frozen half smile. Although she also shows some little snails of hair around her forehead, most of her hair appears covered, surely as a sign of respect for the image she carries and what it symbolizes.

Both images flank a majestic allegory of Spain, the work of the Sevillian sculptor Manuel Delgado Brackenbury. His features are more naturalistic and classic than those of Pérez Comendador, although both coincide in the use of some stylistic resources, such as the use of the wet cloth technique to reveal the shapes of the body. The figure appears standing, with one leg slightly forward, in a posture that gives it great solemnity. He wears a tunic tight under the chest and over his collected hair he wears an open royal crown, a symbol of the Spanish monarchy. She rests her right arm on a large shield of Spain and her right arm on a lion, which in turn rests its paw on a globe, a symbol of Spanish sovereignty. It must be remembered that the lion and not the bull has been the animal that has most symbolized our country throughout its history, appearing profusely since the Middle Ages on a multitude of supports, such as coins, pictorial representations or architectural elements.