The Church maintained a very firm position against Jews and false converts, with numerous preachers travelling around the country to protest against the Hebrew faith, among them the famous Vicente Ferrer. In the same vein, on papal initiative, the so-called Tortosa dispute was organised, a long inter-religious debate that took place mainly in this city of Tarragona at the beginning of the 15th century. Representatives of Christian converts and Jews participated in it. The main aim was to refute any thesis of the Jews and to promote their baptism, sometimes even en masse. In addition, there was no lack of anti-Jewish legal provisions, such as those promulgated in Castile in 1412. According to these, Jews had to let their hair and beards grow to distinguish themselves from Christians and they were forbidden to work as tax collectors or hold any other public office. Among many other limitations, they were also forbidden to treat Christian patients as doctors and to engage in lending with interest.

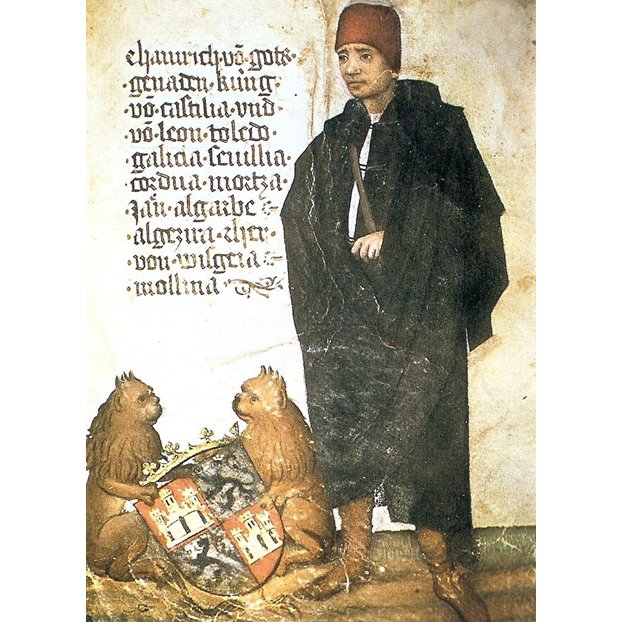

However, in the second half of the 15th century there seems to have been a timid normalisation of the situation and we once again find Jews occupying important positions in the administration, mainly during the reigns of Henry IV of Castile and John II of Aragon.

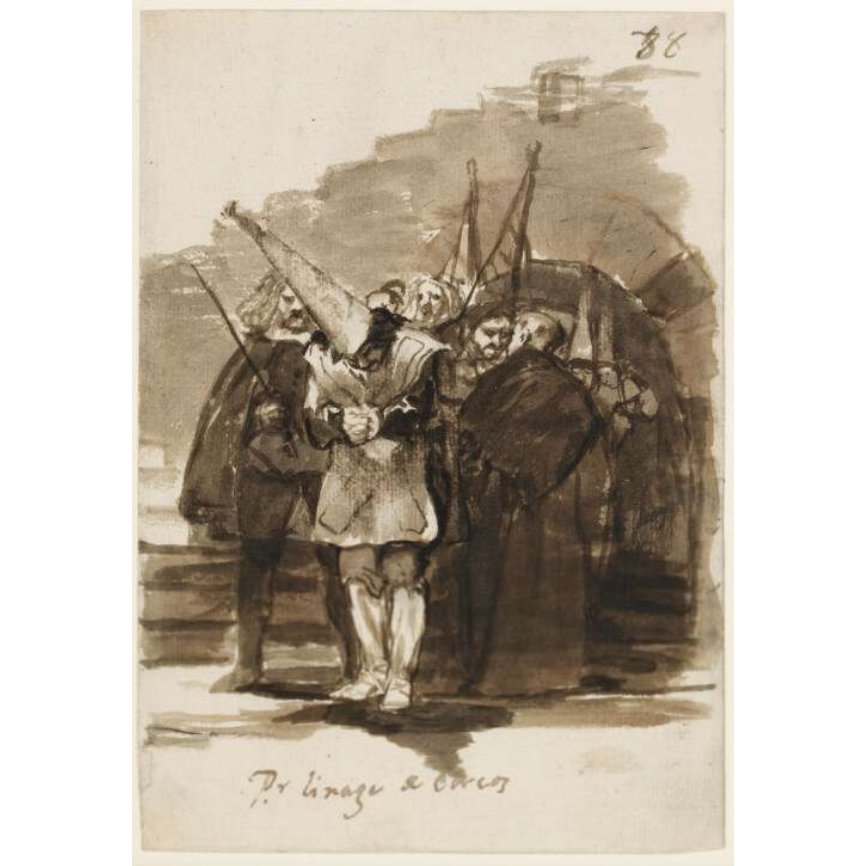

"Predicación de san Vicente Ferrer" (Alonso Cano, 1645). This Valencian preacher belonging to the Dominican order was one of the most determined promoters of anti-Jewish measures at the beginning of the 15th century. Fundación Banco Santander.

However, the road to the end of the Spanish Jewish quarters was already inexorable. The traditional climate of tolerance of the Hispanic kingdoms in previous centuries gave way to a period of constant tension in which the mere presence of Jewish communities was increasingly accepted with increasing difficulty by the rest of the population, often encouraged by provisions in the same direction by the ecclesiastical and secular authorities.

In this general context, Isabel I came to the throne in 1474, married to Ferdinand of Aragon, proclaimed king of his own kingdom just five years later. In this way, a period of joint government of the two main peninsular crowns began, laying the seed of what would become Spain from the 16th century onwards. At that time, the Middle Ages were being left behind, while the legal and institutional foundations of what is a modern State, governed by a centralized monarchy, were being laid. Religious uniformity was understood as an indispensable requirement for this new model of government and this uniformity involved the imposition of the majority faith, which was Christianity.

Furthermore, it is necessary to point out that the decision to expel the Jews was not exclusive to Spain. In fact, our country was one of the last European territories to adopt this measure. As an example, we can cite England, where the Jews were expelled in 1290, or France, where up to four expulsions were decreed between 1182 and 1394. It was, therefore, an ideological current that ran through Europe throughout the Late Middle Ages.

In the case of the Catholic Monarchs, if we look at the content of the Edict in which the expulsion was decreed, it seems that the main motivation was related to the problem of the converts. As we said before, thousands of Jews chose to embrace the Christian faith during the 15th century and, according to various sources, not all of them did so sincerely. To guarantee the orthodoxy of the faith of the new Christians, the Spanish Inquisition was instituted in 1478, directly under the control of the Crown. Two years later, the Catholic Monarchs decreed the strict separation of the aljamas into special quarters to ensure that there was no contact between the new Christians and the Jews, since it was understood that this contact was the most important obstacle that prevented sincere conversions. Finally, on March 31, 1492, the famous Edict of Granada was decreed, ordering the expulsion of the Hispanic kingdoms. Right at the beginning of its exposition of reasons, the edict makes its motivation clear: “It is well known that in our domains, there are some bad Christians who have Judaized and committed apostasy against the holy Catholic faith, the majority of which is caused by relations between Jews and Christians.”

"Expulsión de los judíos de España" (Emilio Sala, 1889). The painter recreates a supposed audience that the Catholic Monarchs granted to a representative of the Jewish community to defend his arguments. On the other side, you can see the general inquisitor, Tomás de Torquemada, vehemently defending the expulsion. Museo del Prado.

The edict allowed Jews who were willing to accept Christianity to stay, but ordered the expulsion of all others, regardless of age.

We further order in this edict that Jews, both male and female, of whatever age, residing in our domains or territories, depart with their sons and daughters, servants, and relatives, small or large, of all ages by the end of July of this year and that they dare not return to our lands and that they take no step forward to trespass in such a way that if any Jew who does not accept this edict is found in these domains or returns, he will be punished with death and confiscation of his property.

There is no way of knowing how many people were forced to leave the country. The historian and theologian Juan de Mariana spoke of 800,000, but that figure is now considered totally absurd. Based on various local studies, current historians place the number of those expelled at around 200,000 people.

En mayo comenzó el éxodo, la mayoría de los exiliados –unas 100.000 personas– encontraron refugio temporal en Portugal (de donde fueron expulsados los judíos en 1497), mientras que el resto se dirigió al norte de África y Turquía, el único país importante que les abrió sus puertas. Algunos encontraron hogares provisionales en el pequeño reino de Navarra, donde todavía existía una antigua comunidad judía, pero allí también su estancia fue breve, ya que los judíos fueron expulsados en 1498. Un número considerable de judíos españoles, incluido el rabino principal Abraham Seneor y la mayoría de los miembros de las familias influyentes, prefirieron el bautismo al exilio, sumándose a los miles de conversos que habían elegido este camino en una fecha anterior. El 31 de julio de 1492, el último judío abandonó España.

Sin embargo, el judaísmo sefardí no había desaparecido en absoluto, ya que casi en todas partes los refugiados reconstruyeron sus comunidades, aferrándose a su antigua lengua y cultura. En la mayoría de las áreas, especialmente en el norte de África, se encontraron con descendientes de refugiados de las persecuciones de 1391. En Israel les habían precedido varios grupos de judíos españoles que habían llegado allí como resultado de los diversos movimientos mesiánicos que habían sacudido al judaísmo español.

Oficialmente, no quedaban judíos en España. Sólo quedaban los conversos, un gran número de los cuales se mantuvieron fieles a su fe original. Algunos cayeron más tarde víctimas de la Inquisición; otros lograron huir de España y regresar abiertamente al judaísmo en las comunidades sefardíes de Oriente y Europa.