The peaceful coexistence of the Christian and Jewish communities, which coexisted in practically all the cities and important population centres, was the dominant trend until the 13th century. However, in the following century this status quo began to crumble and there was growing conflict and rejection of the Jews by the Christians. Episodes of violence became more frequent and reached their peak in the terrible pogroms of 1391.

The reasons to explain this change in dynamics are diverse and complex. Perhaps we should start with the internal fissures and contradictions that existed within the Jewish community. As Julio Valdeón explains, from a social point of view there was a very clear difference between the minority of wealthy Jews, who enjoyed great privileges and had close relations with Christian kings and magnates, and the large mass of small merchants, artisans, farmers, etc., victims par excellence of the wrath of the Christian people. The gap between the two groups was also evident in the area of religious beliefs. The members of the oligarchy, greatly influenced by Averroes and Maimonides, had generally reduced their beliefs to a vague deism. The popular masses, on the other hand, remained faithful to the Mosaic tradition. In the final years of the 13th century, the mystical ideas of the Kabbalah made a strong entrance among the popular sectors. The licentious life of the courtly Jews and their religious lukewarmness were ruthlessly castigated by the pietists. In this way, tensions within the Jewish community itself were accentuated.

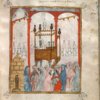

Representation of the Battle of Nájera (1367), one of the episodes of the Castilian civil war that pitted Pedro I against his half-brother, Enrique de Trastámara, between 1351 and 1369. The climate of violence surrounding this conflict was one of the determining factors in the general deterioration of the situation of the Jews in the kingdom. «Chroniques sire Jehan Froissart», Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

But apart from the internal problems of the Jewish community, most of the conflicts with the Christians were due to the nature of the social and economic relations between Christians and Jews. It must be remembered that many Jews held positions in the tax administration, linked, therefore, to the collection of taxes. Some of them were even the highest officials in fiscal policy and guardians of the royal treasury, which aroused enormous suspicions and animosity among Christians, especially in times of crisis when it was difficult to meet tax obligations. It must be remembered that the 14th century was especially turbulent and violent, with the economy in a state of constant deterioration.

The profession of moneylenders to which many Jews dedicated themselves was also problematic. In general, credit is essential for the functioning of a minimally developed economy. Not only the Crown, but also many individuals resorted to money lent by the Jews when the situation made it necessary. However, when the crisis and poverty became widespread, the profits obtained by the moneylenders were seen as indecent by the majority of the population, ending up forming another reason for hatred that was at the direct origin of many of the acts of violence suffered by the Jews.

Finally, we must not forget the religious motives in the strict sense. The Jewish people were constantly identified as the deicide people and were frequently accused of all kinds of behaviour contrary to the Christian faith. Throughout the Middle Ages, the Crown, the Cortes and the Papacy promulgated numerous provisions promoting the segregation of the Jews from the rest of society, as a measure to avoid any kind of proselytism of the Mosaic faith. This anti-Jewish ideological substratum was permanent and in times of crisis or conflict it served as a theoretical framework that supported attacks and outrages against the Jews. On countless occasions the Jews were the scapegoat who paid the consequences in times of social tension.

The first signs of large-scale violence were found in the kingdom of Navarre. When King Charles IV died in 1328, a period of dynastic crisis began which was the perfect setting for these attacks. Groups of "Jew-killers" dedicated themselves to the assault and destruction of numerous Jewish quarters in the kingdom. They did so under the influence of a similar movement that took place in the south of France at the beginning of that century, when groups of extremists dedicated themselves to violently harassing Jewish populations. In addition, there were several preachers encouraging this hatred, such as the Franciscan Pedro Olligoyen, who was singled out as one of the main perpetrators of the outbreak of violence. The authorities managed to contain the attacks in Pamplona and Tudela, where the most important Jewish quarters were located, but anti-Jewish violence broke out in other towns, such as in Funes, San Adrián or Viana. The case of Estella was particularly serious, whose Jewish quarter was completely destroyed.

A couple of decades later, a new anti-Jewish outbreak occurred, this time in the area of Catalonia. In this case, the most direct motivation was linked to the spread of the Black Death. In many places in Europe, especially in the Rhine valley, the arrival of this deadly disease was linked to the spread of rumours that blamed the Jews, accusing them of poisoning the air and water. A few days after the first ravages of the epidemic occurred in Barcelona, in May 1348, there was a violent assault on the Jewish quarter. King Pedro the Ceremonious tried to suppress the outbreak, but could not prevent similar attacks in Montblanch, Tárrega, Cervera, Villafranca del Penedés and Lérida.

In the case of Castile, violence against Jews found its perfect breeding ground in the civil war between King Pedro I and his half-brother Enrique de Trastámara between 1351 and 1369. Enrique's supporters soon spread the unfounded theory that Pedro was not actually the son of the previous king, Alfonso XI, but of a Jew who had given him up for adoption to the monarch. Pedro was frequently referred to as "the Jew" and the large number of Jews who held positions of responsibility at court was denounced as a symbol of degradation. In this context of general conflict, numerous Castilian Jewish communities suffered attacks, sometimes at the hands of foreign combatants who participated in the conflict on both sides, such as the French under the command of Bertrand du Guesclin or the English under the orders of the Black Prince. This occurred, for example, in Briviesca, Aguilar de Campoo or Villadiego. On other occasions, it was the inhabitants of the cities themselves who turned against the Jews, as in Valladolid, Segovia, Ávila or Toledo.

The latter city suffered especially from this war even after its end. Shortly after ascending to the throne, Henry II imposed an enormous tribute on the Jews of Toledo, plundered and impoverished, as punishment for their loyalty to Peter. He ordered that all property, movable and immovable, belonging to the Jews of Toledo be sold at public auction and that all the latter, both women and men, be imprisoned and starved and tortured in other ways until they had raised this immense sum.