Today, most historians point out that the first Jewish communities settled in the Peninsula during the 1st and 2nd centuries, specifically after the destruction of Jerusalem in 70, during the reign of Vespasian, and after the subsequent repression of the Bar Kochba rebellion in 134, with Hadrian as emperor. Within the dispersion that followed these events, it is very likely that an undetermined number of Hebrew families left the Holy Land to end up settling in Hispania. In fact, several passages in the Talmud and the Midrash (Leviticus Rabbah) indicate that during the reign of these emperors the forced transfer of Jewish prisoners to the Peninsula was ordered. These testimonies show an early settlement, whether voluntary or involuntary.

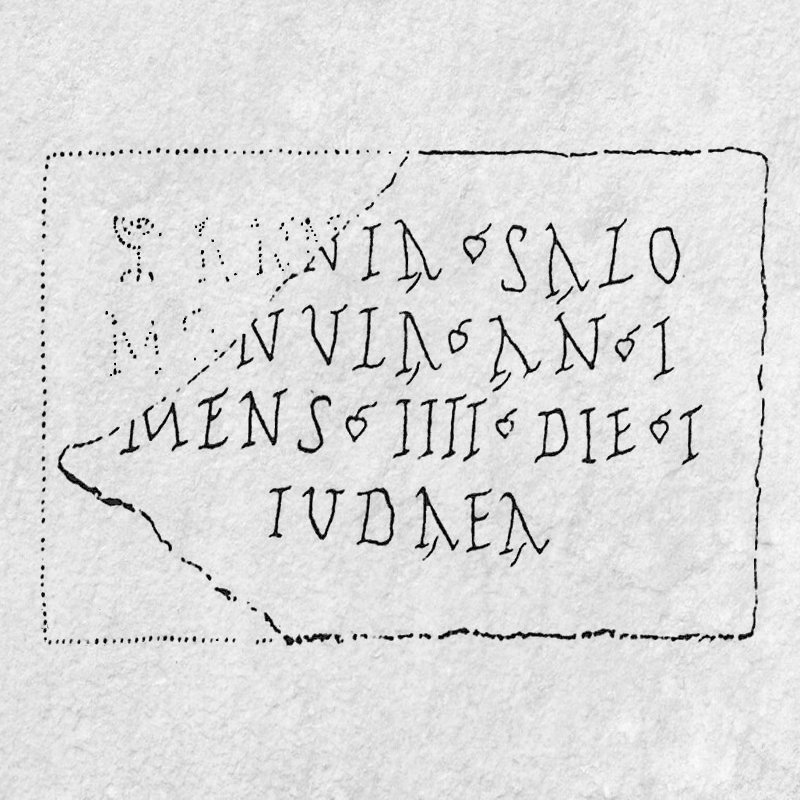

The oldest documentary evidence found in Spain is an inscription known as the Epitaph of the Jewess Annia Salomonula. This is the tombstone that covered the burial of a girl in the town of Adra in Almería. On it we can read:

[An]nia · Salo/[mo]nula · an(norum) · I / mens(ium) · IIII · die(rum) · I / Iudaea

Annia Salomonula, one year, four months, one day, Jewish.

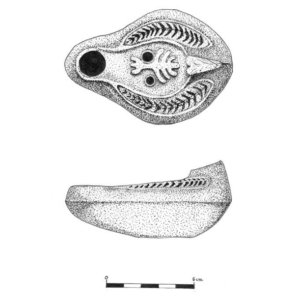

There is archaeological evidence that supports the claim that Jewish communities were numerous during the late Roman Empire, when the first Christians were also found in the cities of Hispania. For example, several lamps engraved with the menorah or Jewish seven-branched candelabrum have appeared in places as diverse as Mérida, Toledo, Cástulo (Jaén), Águilas (Murcia) or Palma de Mallorca, all of them dating from between the 4th and 5th centuries. From the same period, a curious white marble font found in Tarragona is preserved in the Sephardic Museum of Toledo. It is also decorated with the menorah, as well as other symbols represented schematically, such as the tree of life. It has the peculiarity of having inscriptions in Latin, Greek and Hebrew. In the latter language one can read “Peace upon Israel and upon us and upon our children”.

Lucerne found at the late Roman site of El Molino (Águilas, Murcia). Hernández García, Juan de Dios. "La necrópolis tardorromana del Molino". Memorias de Arqueología 13, 1998.

Lucerne found in the Archaeological Complex of Cástulo, Jaén (5th century). Google Arts & Culture.

Lucerne from Toledo (5th century). Museo Sefardí de Toledo.

When the Roman Empire collapsed in 476, Hispania became a monarchy ruled by the Visigoths, a people of Germanic origin who had entered the Peninsula several decades earlier. It does not seem that the first Visigoth kings were especially belligerent in religious matters and in general the Jewish communities continued to function in a similar way to that of the last centuries of the Empire. However, everything changed when King Recaredo adopted Catholicism as the official religion (587). He soon approved a series of anti-Jewish provisions, which were reinforced by the decrees of the Council of Toledo in 589. Among other measures, Jews were prohibited from having Christian slaves, holding public office, as well as marrying or having sexual relations with Christians.

With subsequent monarchs, situations of repression alternated with others of a certain relaxation, so many Hebrews adopted Christianity to avoid problems in difficult times and then returned to Judaism when the situation improved. This caused the positions of the Catholic hierarchy to become even more extreme and the different Catholic councils held in Toledo only corroborated and expanded the anti-Jewish laws promulgated by the crown.

"La conversión de Recaredo" (1888). Painting by Antonio Muñoz Degrain recreating the moment when Recaredo abandons Arianism to adopt the Catholic faith. Senado de España.

The reign of Sisebuto (612-621) marks a high point in the repression, marking a harsh line against the Hebrew people that will be the most common tone in the rest of the history of the Visigothic kingdom in the Peninsula. As Joseph Pérez points out in his “The Jews in Spain”, Sisebuto orders the Christians to be freed from all relations of dependence with respect to the Jews who are forced to give up their slaves and servants; Jewish proselytism is punished by the death penalty and the confiscation of property; the children that Jews may have with Christian slaves must be educated as Christians. (…) Finally, Sisebuto intends to force the Jews to convert to Catholicism or, if not, to leave Spain. The number of those who were then expelled has been calculated in many thousands and that of those baptized in 90,000, but they were probably much less. Since then, converts and Jews were excluded from public office on the grounds that it was intolerable that they had authority over Catholics.

Imaginary portrait of King Sisebuto, painted in 1854 by the Sevillian painter Mariano de la Roca y Delgado. Museo del Prado.

Despite the severity of these measures, the anti-Jewish policy had not yet reached its most extreme and violent levels. Around 638, Chintila decreed the prohibition of living in the kingdom for anyone who was not Catholic. In the second half of that same century, Recesvinto ordered the death of Jews by stoning or burning, and shortly after, Égica decreed the enslavement of both Jews and converts. The degree of compliance with these measures varied depending on the time and the city in question, but as a whole they created an unbreathable atmosphere for the Jewish community in Hispania, increasingly marginalized socially and more exposed to increasingly frequent outbreaks of violence.

Despite the severity of these measures, the anti-Jewish policy had not yet reached its most extreme and violent levels. Around 638, Chintila decreed the prohibition of living in the kingdom for anyone who was not Catholic. In the second half of that same century, Recesvinto ordered the death of Jews by stoning or burning at the stake and, shortly afterwards, Égica decreed the enslavement of both Jews and converts. The degree of compliance with these measures varied depending on the period and the city in question, but as a whole they created an unbreathable atmosphere for the Jewish community in Hispania, increasingly marginalised socially and more exposed to increasingly frequent outbreaks of violence.