The term Sephardic refers both to the Jews who historically inhabited the Iberian Peninsula (Sepharad), and to the descendants of the Jews expelled from Spain in 1492 and from Portugal in 1497. On March 31 of that year, an edict of expulsion was issued against all Jews who refused to accept Christianity. Some accepted conversion, but others, around 200,000, left for North Africa, Italy and especially Turkey, where they were warmly welcomed by the Sultan. Thus the Sephardic diaspora was created, a dispersion within a dispersion that not only looked to Israel as its homeland, but had been indelibly marked by a long stay in Spain. The exiles brought with them the language and songs of Spain, which they faithfully preserved, and even many of the foods characteristic of the Peninsula. They also bore Spanish personal and family names, and their worldview had been shaped by the customs and conduct of their Spanish neighbors.

Among these settlers were many who were descendants or heads of wealthy families and who had held prominent positions in the countries they had left. Some had been state officials, financiers, and owners of mercantile establishments. There were also doctors or scholars who had served as teachers in secondary schools. The many sufferings they had endured for the sake of their faith had made them more self-conscious than usual. They sometimes considered themselves a superior class, something like the nobility of Judaism. This sense of dignity possessed by the Sephardim was manifested in their general behavior and in their scrupulous attention to dress.

1. Saint-Jean-de-Luz. 2. Biarritz. 3. Bayonne. 4. Tartes. 5. Bordeaux. 6. La Rochelle. 7. Nantes. 8. Rouen. 9. Paris. 10. London. 11. Bristol. 12. Dublin. 13. Brussels. 14. Antwerp. 15. Rotterdam. 16. The Hague. 17. Amsterdam. 18. Emden. 19. Glückstadt. 20. Altona. 21. Hamburg. 22. Copenhagen. 23. Marseille. 24. Lyon. 25. Turin. 26. Genoa. 27. Milan. 28. Padua. 29. Venice. 30. Ferrara. 31. Lucca. 32.Pisa. 33.Livorno. 34.Florence. 35.Ancona. 36.Rome. 37.Naples. 38.Palermo. 39.Messina. 40.Split. 41.Vienna. 42.Budapest. 43.Belgrade. 44.Ragusa. 45.Sofia. 46.Thessaloniki. 47.Adrianopolis. 48.Istanbul. 49.Arta. 50.Athens. 51.Smyrna. 52.Krakow. 53.Zamosc. 54.Beirut. 55.Damascus. 56.Acre. 57.Safe. 59.Tiberias. 60.Jerusalem. 61.Gaza. 62.Cairo. 63.Alexandria. 64.Tunis. 65.Algiers. 66.Oran. 67.Fez.

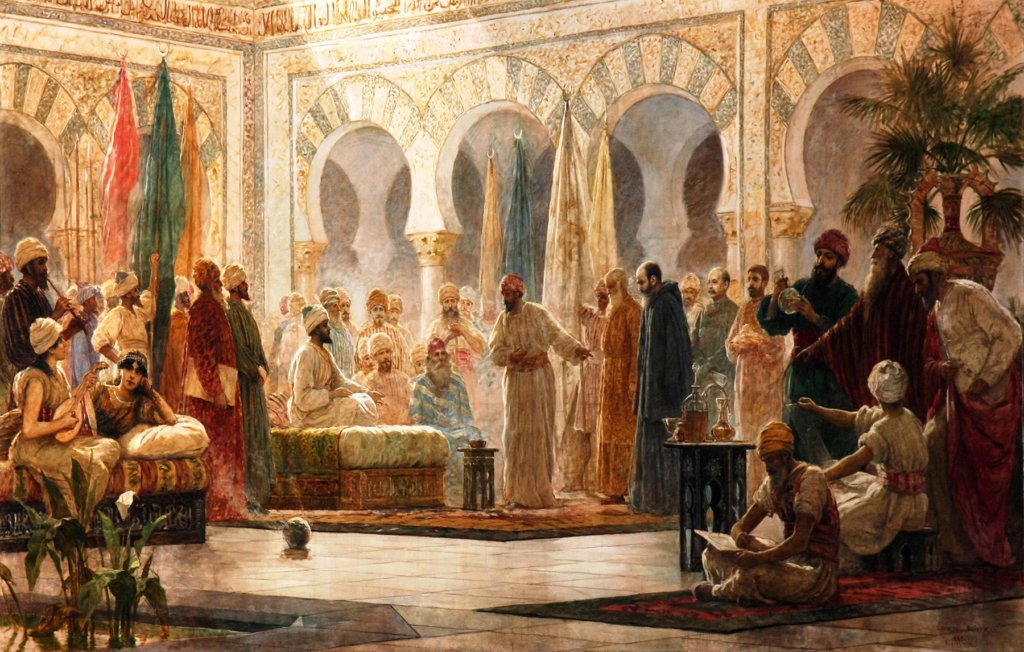

The number of Sephardim who have rendered important services to different countries is considerable, from Samuel Abravanel (financial adviser to the viceroy of Naples) to Benjamin Disraeli. Among other names mentioned are those of Belmonte, Nasi, Pacheco, Palache, Azevedo, Sasportas, Costa, Curiel, Cansino, Schonenberg, Toledo, Toledano and Teixeira.

The Sephardim occupy the first place in the list of Jewish doctors. Many of them won the favor of rulers and princes, both in the Christian and Muslim worlds. The fact that the Sephardim were chosen for prominent positions in all the countries in which they settled was due to the fact that Spanish had become a world language through the great expansion of Spain since the end of the 15th century. From Tangier to Salonika, from Smyrna to Belgrade and from Vienna to Amsterdam and Hamburg, they preserved not only Spanish dignity but also the Spanish language. Thus was born the Judeo-Spanish or Ladino language, preserved with great tenacity from generation to generation to the present day, with today some 150,000 speakers in Israel alone.

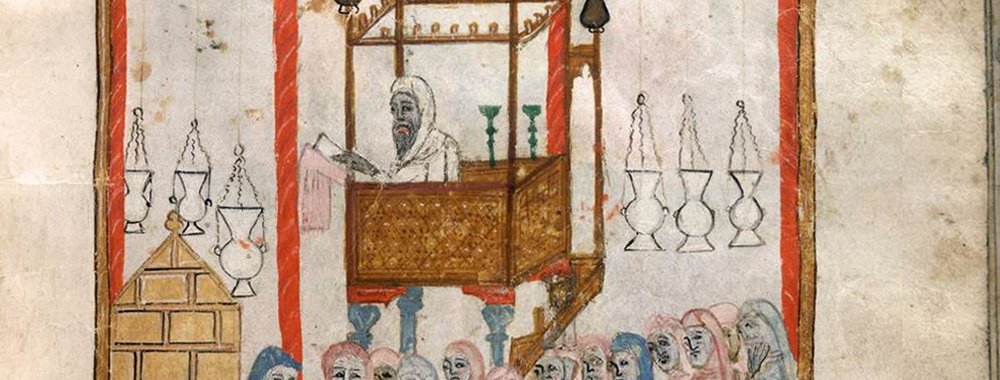

For a long time the Sephardim were actively involved in Spanish literature. They wrote in prose and rhyme, and were authors of theological, philosophical, literary, pedagogical and mathematical works. The rabbis, who, like all Sephardim, placed great emphasis on a pure and euphonious pronunciation of Hebrew, delivered their sermons in Spanish or Portuguese; several of these sermons appeared in print. Their thirst for knowledge, together with the fact that they interacted freely with the outside world, led the Sephardim to establish new educational systems wherever they settled; they founded schools in which the Spanish language was the medium of instruction.

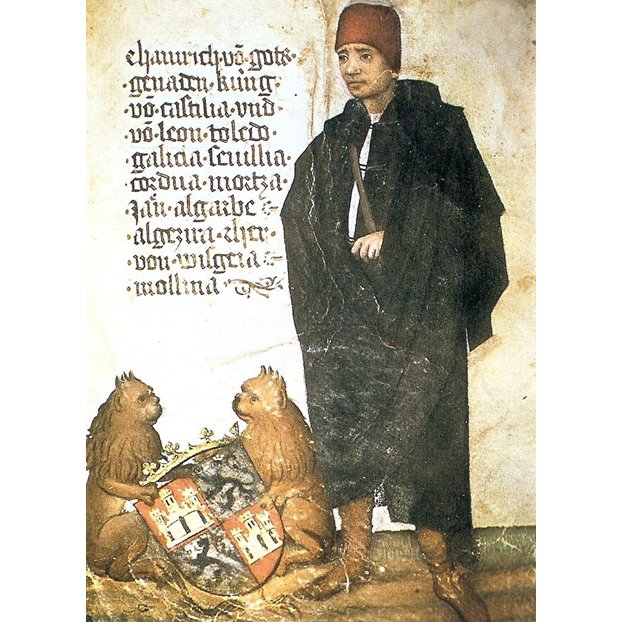

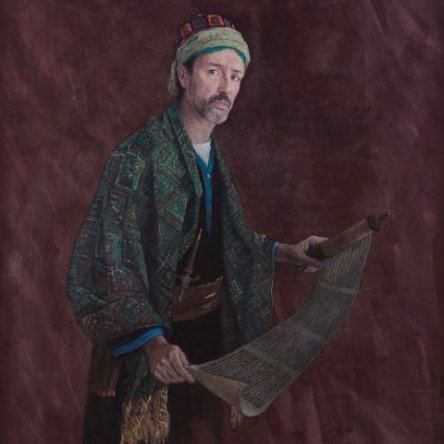

Sephardic Jewish couple in traditional dress in Sarajevo at the end of the 19th century. Wikimedia Commons.

In Amsterdam, where they were especially prominent in the seventeenth century on account of their numbers, wealth, education, and influence, they established poetical academies after Spanish models; two of these were the Academia de los Sitibundos and the Academia de los Floridos. In the same city they also organized the first Jewish educational institution, with graded classes in which, in addition to Talmudic studies, instruction was given in the Hebrew language.

The Sephardim have preserved the romances and the old melodies and songs of Spain, as well as a large number of old Spanish proverbs. Several plays for children, such as "El Castillo," were very popular with them, and they still manifest a fondness for the dishes peculiar to Spain, such as "pastel," or "pastelico," a kind of meat pie, and "pan de España," or "pan de León."

Mainly in those families that kept Ladino as their main language, the most common names were those of Spanish origin, such as Aleqría, Ángel, Ángela, Amado, Amada, Bienvenida, Blanco, Cara, Cimfa, Comprado, Consuela, Dolza, Esperanza, Estimada, Estrella, Fermosa, Gracia, Luna, Niña, Palomba, Preciosa, Sol, Ventura y Zafiro; y apellidos españoles como Belmonte, Benveniste, Bueno, Calderón, Campos, Cardoso, Castro, Curiel, Delgado, Fonseca, Córdoba, León, Lima, Mercado, Monzón, Rocamora, Pacheco, Pardo, Pereira, Pinto, Prado, Sousa, Suasso, Toledano, Tarragona, Valencia y Zaporta.

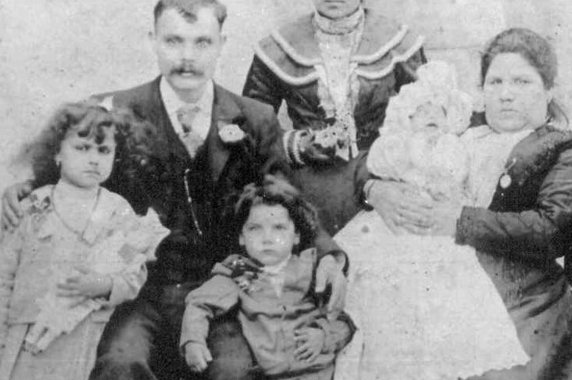

Family of Sephardic Jews in Argentina at the beginning of the 20th century. Wikimedia Commons.

For a long time, Sephardim married predominantly other Sephardim. They also made an effort to maintain the particularity of the ritual with respect to the Ashkenazi one. Wherever Sephardic Jews settled, they grouped together according to the country or district from which they had come and organized separate communities with legally promulgated statutes. In Constantinople and Salonika, for example, there were not only Castilian, Aragonese, Catalan, and Portuguese congregations, but also in Toledo, Cordoba, Evora, and Lisbon.

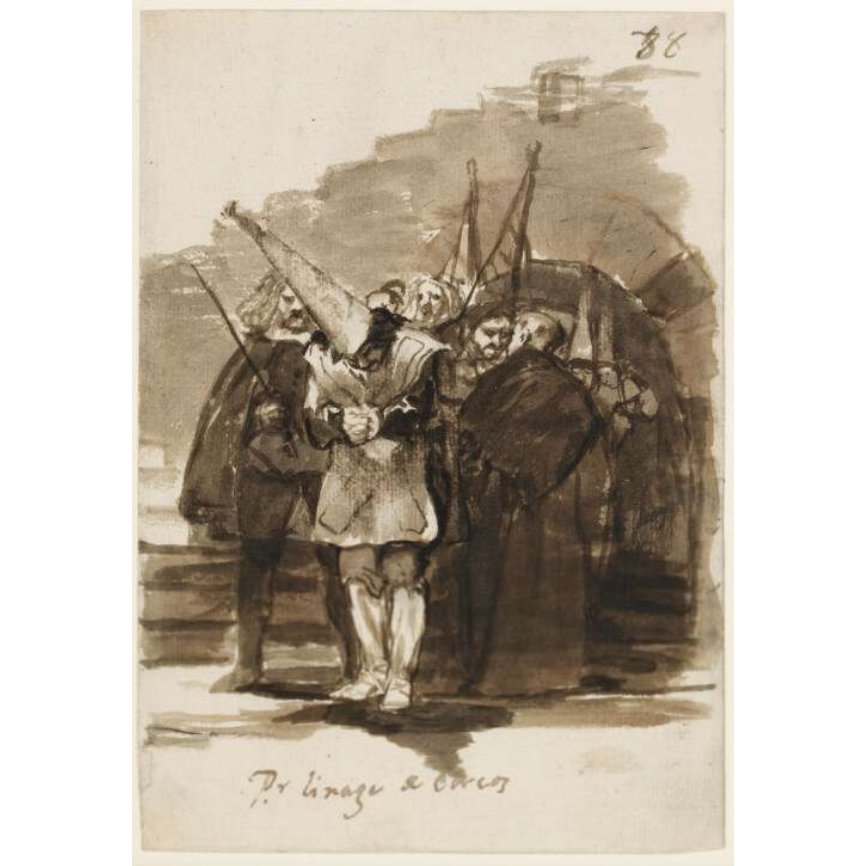

Great authority was given to the president of each congregation. He and the rabbinate of his congregation formed the "ma'amad," without whose approval (often written in Spanish, Portuguese, or Italian) no book with religious content could be published. The president not only had the power to make authoritative resolutions regarding the affairs of the congregation and to decide communal questions, but he also had the right to observe the religious conduct of the individual and to punish anyone suspected of heresy or of transgression of the laws. He often proceeded with great zeal and with inquisitorial severity, as in the cases of Uriel Acosta and Spinoza in Amsterdam.

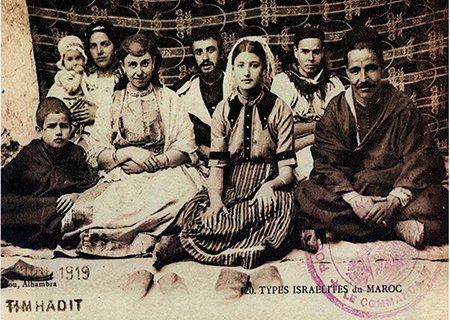

Group of Sephardim in Morocco around 1919. Wikimedia Commons.